2024

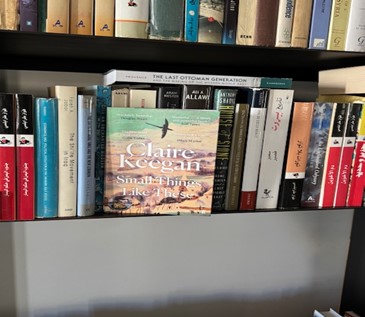

The cover photo needs no explanation. A salute to the colors of the watermelon, red, green, white, and black today and forever.

Some housekeeping before I start with this first post of 2025: a few readers have reached out to me expressing frustration that they are unable to like my posts. That’s because what you receive in your inbox from substack is an email of the post. Click on the heart or the title and it will take you to the blog itself. There, by all means click away!

****

“It was all furr fookin’ no’tin.” These would have to be the most dreaded four words for any freedom fighter or revolutionary. All the sacrifice and blood. All those years in the hard fight; the friends who died before your eyes, so very young and so utterly beautiful as they yielded to their end. The families that grieved their loss, the orphaned children who grew up in their heroic shadow, wanting to be just like them, or hating them for loving a cause more dearly than life itself.

When I watched Maxine Peak’s Dolours Price blurt out these words in her Irish lilt in Say Nothing, I thought, my God, the seemingly simple words that echo painfully across decades, countries, and struggles. Price had once been a member of the IRA’s Unknowns, the tight-knit unit who “took care” of informants and traitors (real and otherwise) in Northern Ireland during the Troubles between the 1960s and ‘90s. She and her sister had also served years in prison for bombing London’s Old Bailey in 1973.

Price committed these words to journalist Patrick Radden Keefe’s recorder and to posterity because she was very unhappy about the peace process then underway between Ireland, England, and Northern Ireland’s warring parties, which eventually led to 1998’s Good Friday Agreement. Her verdict is scathing as all diehard revolutionaries’ judgements are. Compromise over precious dreams in sight of such extraordinary surrender to a cause is tantamount to betrayal.

When I was watching Say Nothing, dramatically adapted from Keefe’s best-selling book, I was also, by sheer happenstance, on the last few pages of Shafiq Ghabra’s Hayat Ghayr Aminah (An Unsafe Life). The memoir is essentially of his time as a leader of al-Jarmaq, the Palestinian youth brigade that was formed in Lebanon, in 1977, under the umbrella of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). It stood out in those years of the Palestinian resistance because of the seriousness, decency, and dedication of its warriors.

In demeanor, at least, Price and Ghabra were different models of radical. Those who knew Ghabra describe him to me as ever the gentleman. It shows everywhere in the text, even in his criticisms of the PLO. And yet the pages are gracious hosts of his disappointments. Palestinian fighters’ “courage on the battlefield and their immorality and readiness to violate people and property,” baffle him. And so do Yasser Arafat’s copious wrongs: his notorious habit of overestimating his strength, of misreading his Israeli enemy, of misunderstanding the political moment and its weight. At one point, with much affection, he quotes his comrade Jarmaq commando Ziab al-Ali, aka Abu al Fateh: “The Palestinian state that will be established one of these days will be Somoza country”––that would be, of course, the very corrupt Anastasio Somoza Debayle who ruled Nicaragua from 1967 to 1972 and from 1974 to 1979.

One suspects that Ghabra, who published the memoir in 2012, 18 years into the Oslo Accords, meant al-Ali’s censure to be his. But Ghabra just couldn’t bring himself to utter Price’s very words: “It was all furr fookin’ no’tin’.” How could he, with so many brothers and sisters in arms having sacrificed their lives for Palestine? In the last paragraph, he pays tribute to them as if in consolation for all that he had written in condemnation of a liberation movement that failed its people’s dearest aspirations:

On those hills and valleys and in those alleyways, the spirits met and will continue to meet in eternal love for a wounded Arab cause and the human toil for justice shouldered by an Arab youth with determination and forbearance. I bow before all those who carved on the walls of our cause and deep within my being and memory a story worthy of telling to generations that still dream. Peace be upon their pure souls (the translation is mine).

The Good Friday Agreement and the Oslo Accords, as with the Irish struggle and the Palestinian one, are often cited as studies in contrasts: success and failure; peace and apartheid. Historian Rashid Khalidi, who at present is researching the very matter, is sure to weigh in with his own argument.

At first glance, though, you would think that there is hardly anything a freedom fighter has in common with his arche enemy, the invading soldier. Not so. There are such sharp divides, such clashing predicaments, such depth to the alienations that separate these antagonists, we forget the trauma that makes one of their suffering; those dark affinities the occupier and occupied, the colonizer and colonized, the tormentor and tormented share that reshape life or ruin it outright.

“I sent them a good boy, they gave me back a murderer,” said the mother of Paul Meadlo, a Vietnam veteran, to Seymour Hersh when he came calling in Western Indiana, in 2015. Meadlo, a member of Charlie Company, had partaken in the 1968 Mai Lei massacre, which Hersh had uncovered in 1969. The journalist had barely entered the house, when Myrtle Meadlo made her declaration; a mother’s cri de coeur about what a “morally groundless, strategically lost war” had done to her once good old American boy.

Hersh’s “Scene of the Crime,” his last substack post for 2024, was actually first published in the New Yorker in 2016. The years have not aged this stunning piece. In its rich accounts of that terrible war are facsimiles of what we are witnessing now in Israel’s atrocities in Gaza. On that fateful morning of March 16, 1968, two massacres were committed. Charlie Company did their unforgivable deed in My Lei, and Bravo Company did theirs in My Khe, a nearby settlement. The horrors of that day play like sneak peaks of those vaporizing the Palestinians of Gaza today:

The…count no longer in dispute is five hundred and four victims, from two hundred and forty-seven families. Twenty-four families were obliterated—–three generations murdered, with no survivors. Among the dead were a hundred and eighty-two women, seventeen of them pregnant. A hundred and seventy-three children were executed, including fifty-six infants. Sixty older men died… four hundred and seven victims in My Lai 4 and ninety-seven in My Khe 4.

“It was revenge, that’s all it was,” Paul Meadlo told Hersh during their hours-long conversation in 2015. He didn’t want to stop, it seemed to Hersh, “clearly desperate to regain some self-respect.” We’re not privy to the details of the encounter, but I can’t imagine Meadlo’s demons as much different from those who haunt the anonymous Israeli soldier’s confessions last November in Haaretz:

No matter how hard Israel tries to make it disappear, to blur it, the destruction in Gaza will define our lives and our children’s lives from now on. It’s testimony of unbridled rampaging. A friend wrote on the wall of the operations room: “Quiet will be answered by quiet, Nova will be answered by Nakba.” The army commanders have adopted this graffiti.

In “Shoah,” Pinkaj Mishra’s seminal essay in the London Review of Books on the profound meaning of Gaza, he reminds us that poet Aimé Césaire and independent India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru had long ago recognized “Nazism…as the radical ‘twin’ of Western imperialism.” In the book of reckonings, in fact, there has never been a contrast more jarring than the West’s sonorous penance for the Holocaust and its refusal to atone for its sins against the multitudes it brutalized, enslaved, and colonized around the globe.

Which makes all the more ironic Israel’s self-described role as the West’s bastion in the East. The irony reaches its meanest, when the Jewish state, whose raison d’être became truly compelling in the penumbra of the slaughter of Jews in Germany, designates itself as the sharpest instrument of Western interests––whether the West likes it or not. And judging by the scandalously faint protests emanating from its officialdom, the West appears to like it just fine.

“Our enemies are your enemies, our fight is your fight, and our victory will be your victory,” Prime Minister Bibi Netanyahu blared at the US Congress last July, as the IDF was burning its way through Gaza. I seriously doubt Bibi had in mind only to magnanimously share the spoils of Israel’s conquests. His was just as much a warning that if Israel goes down for its war crimes, the West goes down with it. In that threat, he was making 2024’s surest predication: the collapse of the entire Western order.

In one particularly illuminating Ezra Klein podcast on May 17, 2024, Yale Law School Professor Aslı Ü. Bâli, deconstructs with precision and care every pretext Israel has used in justifying its merciless war on the Palestinians. Through such analysis, one truly begins to have the full measure of the extent to which Israel’s violations have shaken the very foundations on which the West has constructed its elevated post-World War II narrative––one clearly meant for it but not the rest of us.

Optimism as we lie submerged in 2024’s wreckage is foolhardy business. But there are always exits for those who endeavor. And endeavor, we all must. In an unusually insightful conversation between Peter Beinart and Professor Raef Zraik of Israel’s Ono Academic College, I glimpsed such pathways for Israel-Palestine.

There you have them! My favorite series in 2024: Say Nothing. My favorite memoir: Shafiq Ghabra’s An Unsafe Life. My favorite essays, Mishra’s Shoah, Hersh’s The Scene of The Crime, and the anonymous Israeli soldier’s entreaty: A Soldier’s Warning: What I Saw in Gaza Will Define Our Future. My favorite podcasts Ezra Klein and Peter Beinart’s conversations with professors Asli Ü. Bâli and Raef Zraik, respectively.

As for the photo that, to my mind, is one of the most eloquent expressions of this past year’s anguish, please do rest your eyes below on photographer Moises Saman’s shot of mourners at the funeral ceremony of disappeared Syrian activist Mazen al-Hamada, whose body was finally discovered near Damascus after Bashar Assad’s fall. The snapshot was part of the photo booth that accompanied Jon Lee Andersen’s New Yorker article, “Syria Faces Its Past and Its Future.”

****

On Another Note

Finally, my favorite novel, which, as it happens, is also situated in modern-day Ireland. I have something for the Irish, for all the obvious reasons, among them their love of watermelons.

Kind gestures rarely constitute acts of bravery; they’re sweet by their very nature and courage by its own is extraordinary. In Claire Keegan’s 2021 novel, Small Things Like These, the two are on such fine display, they leave you quite the mute. I am in awe at how such a delicate, small book could be such an exquisite education.