The Eclipse of NGOization?

You’re looking at a well camouflaged Lebanese girl during the 2019 protests write on one of Beirut’s columns: dawlet ‘arsat: a state of crooks. I am using a euphemism here. A more accurate translation would be degenerates, pimps even.

There is panic in the air. You can smell it. Not in Gaza. There, panic is for the birds. It doesn’t measure up to the despair and dread.

The panic I sense is among others, elsewhere. It’s not the fear we’re used to; the fear of sectarian violence, or another Israeli war, or more fragmentation. It’s the fear of being discarded. The fear of many NGOs in the Levant, in Iraq, in Egypt, in other North African countries, that they have been forsaken by their Western chaperones.

The money is drying up from practically every source. USAID dominates the headlines, but the crisis is much deeper and older than Trumpian impatience with foreign assistance. It’s also more complicated than the genuinely life-saving programs that have been left crippled by the drastic cuts. Much like the advent of Neoliberalism in the 1980s was a harbinger of the rise of NGOization, especially in the Global South––how I hate that term!––so is the waning of this ideology a portent of the eclipse of the age of NGOs.

It’s a hell of a story that has been unfolding over the course of the last 40 years. It started in the West––where else? One of Neoliberalism’s heroes is the economist Milton Friedman. His Chicago Boys, named after the University of Chicago where Friedman taught, were quite the pack back in the day, traveling the world to set political economies straight––or not.

The economic model’s biggest champions in the West were Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. Outside it, Chile’s Augusto Pinochet was the trailblazer, with the help of Friedman and the boys in the mid-1970s. Its precepts are quite straightforward: open borders, privatization, free markets, free trade, a rolledback state, a very tight public belt, a very tamed social safety net.

From the start, in geographies like the Arab region outside the Gulf, where the neoliberal doctrine spread, the enemy was organized politics: independent trade unions, political parties, social movements, professional associations…Simply put: anything that spelled mass mobilization and collective action as the state shrank its social care and patronage.

That was convenient for regimes like ours whose repressive systems had already deprived grassroots politics of its purchase. In their place, Neoliberalism deployed its own cavalry: in the main, international government and non-government agencies and local NGOs, each performing its role as donor and recipient, sponsor and executor, policymaker and frontliner. Its buzzwords across continents were the same: gradual reform, peaceful change, self-help, empowerment… All of which was also convenient for our regimes and, as it happens, to us, the people who came from all walks of the good life, some peddling foreign agendas, others clueless but decent and well-meaning, still others very engaged and serious.

I have written about this often and at length, last in This Arab Life:

In countries with robust dictatorial instincts, where repression to organized resistance is routine, you couldn’t hope for a better alternative to popular defiance than civil society’s NGOs. The state got its fleet of harmless humanitarians, the humanitarians got their safe activism and the West got its supposed gradual reforms that assured a “peaceful and stable” order. The strugglers, meanwhile, got their self-help programs, all designed to ease the suffering and/or equip them as full-fledged members of this brave new world.

The history, of course, is not as unadorned as the above paragraphs imply. All I can do in this tiny space is give the heart of this now very urgent matter an airing. And the heart of it in our neighborhood is a rather sorry one. For decades, our so-called civil society, composed mostly of NGOs covering the whole spectrum of causes, has been almost entirely dependent on foreign aid from private and public Western donors.

It couldn’t be any other way for many Arab NGOs, frankly. There was no sustainable local source of support. The private sector was generally very traditional and nonstrategic in its giving and the state was, in any event, intolerant of any funding that remotely involved civil or human rights.

But the numbers alone give a measure of Neoliberalism’s success in making NGOization the main feature of civil society’s chaotic ecosystem in the region. Jordan is a glaring showcase. In the 1960s, it had only 50 organizations, mostly charities; by 2015, NGOs topped 4,200, their members constituting 43% of the working-age population. Hence, the palpable panic in Amman when Trump reduced USAID to a shell.

Now the West, whose own populace has had enough of Neoliberalism’s unbridled capitalism, is signaling to the rest of us that the era of NGOization is fading. Such signals come after years of hardship in the aftermath of the 2011 Arab uprisings which saw alarmed authorities clamp down on all sources of external and internal funding; made worse recently by the West’s moral failures on Israel’s genocide in Gaza and its attempts to censor local NGOs’ anti-Israeli advocacy. In the last three months, I’ve had calls from human rights groups, education initiatives, social sciences institutions, poverty alleviation projects, arts programs…to discuss a homegrown base of supporters and funders.

The pivot, albeit forced, is healthy and necessary, but the solution is neither obvious nor easy. The truth is that sustained and generous homegrown funding is very difficult. Neither our private sector nor our public and private foundations appear to care for this kind of philanthropic investment.

In such a hostile climate, one might imagine soon an ecosystem that lies in ruins, the way entire landscapes do in the aftermath of a tempest. The implications for the state, forever in retreat in geographic reach and policy in, say, the Levant and North Africa are difficult to discern.

For the NGOs themselves, it will feel like a purge. By the end of it, only the strong and agile and deeply rooted will survive. Over the long term, we may look upon this moment as the time when NGOization gave way to a new epoch in activism––more autonomous, creative, resilient, strategic––the name of which is as yet unbeknownst to any of us.

****

On Another Note

I’ve long ago thought that the mysteries of this universe, although very compelling to me, are well above my pay grade. I therefore chose to satisfy myself simply with the majesty of it all.

On the matter of the afterlife in all its religious and non-religious expressions, I have also maintained since perhaps the age of 18 years old that my preoccupation in earthly affairs is probably a less frustrating endeavor. Sooner than I would like, I told myself, I will find out what awaits me after that last thump of the heart. And so, over the ensuing years, what I read about the question, I read more as an intellectual exercise than a personal quest.

I wasn’t sure what to expect when I sat back to listen to Ezra Klein and conservative author and columnist Ross Douthat conversing on “Trump, Mysticism and Psychedelics.” Douthat, a catholic man of strong faith, has just published Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious. As it turns out, the conversation was well worth my afternoon. I suspect it will be well worth yours.

Have a listen!

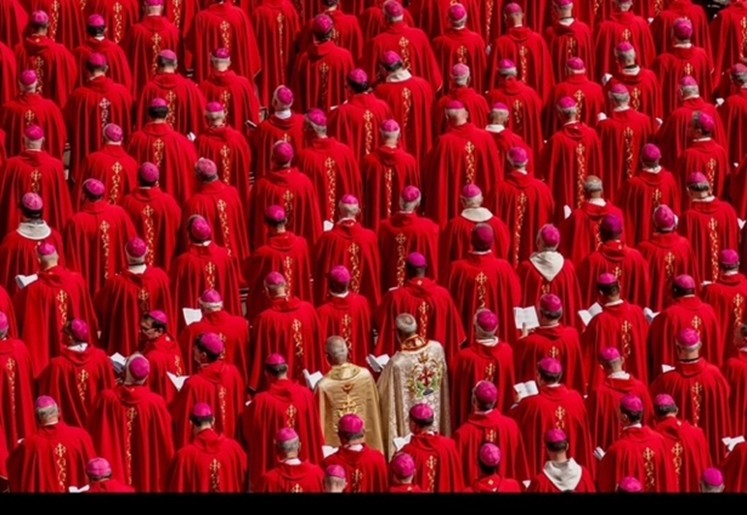

Appropriately, here’s one marvelous visual depiction of the sublime. My favorite photo of the week.