Déjà Vu In The Levant?

You’re looking at Beirut’s Burj in 1952. I cannot lie. I would have very much liked to walk those streets and live that life.

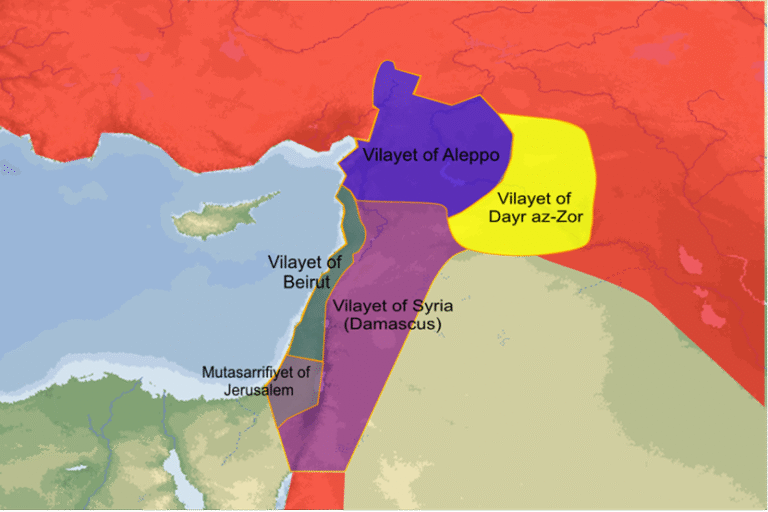

In the 1920s, France, the mandatory power in control of Syria, spent the better part of its ill-conceived mandate by turns slicing up and restitching Greater Syria. Its first attempt in 1920-1921 produced five statelets: the state of Aleppo, the state of the Druze, the state of the Alawites, the state of Damascus, and Greater Lebanon. Mount Lebanon attained its “greater” status courtesy of the coastal cities, the Bekaa valley, and the south, which France saw fit to add to it.

When this arrangement very quickly failed to bring the Syrian people to heel, the French, in 1922, created the Syrian Federation that pulled together Aleppo, Damascus, and the Alawite region. When that very quickly proved unworkable, they established the state of Syria in 1925, but placed the Druze and Alawite areas under a separate administration. This policy stumbled its way into 1936, when the two autonomous locales gradually joined the rest of Syria under one centralized state.

Much has changed in the Levant in the last 100 years: coups d’état, wars, civil wars, conquests, ethnic cleansing, genocide, the establishment of new nations, the emasculation of very old ones, the eclipse and advent of regional powers, the surge and decline of superpowers, the ebb and flow of non-state actors, the birth and death of ideologies, of political parties…

And look at Syria now! Look at us in Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel-Palestine! Not surprising, I suppose, that everything about and between us remains negotiable: our borders, our national identity, our resources, our sense of belonging, our autonomy. In the case of the Palestinians, even our right to exist as a people, a nation.

Among colonial botch ups, we certainly shine. It is patently true that we added our own homegrown ones to this original sin. But it bears repeating as well that in the mess we made, we had many friends; in the cleanups we embarked upon, many enemies.

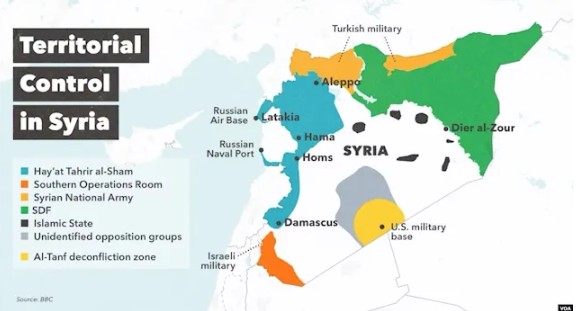

Post-Assad Syria is on the brink of sectarian strife, by all appearances. Its epicenter is the country’s significant coastal areas. Ironically, it’s one of the geographies that historically was a showcase of coexistence and cultural richness. The conflict’s momentum is hard to gauge at the moment, but its victims are already thousands of innocents. The culprits would seem to be marauding Salafi Jihadi militias. But the nascent regime of Ahmed al-Sharaa owns much of the blame for viciously attacking and bombing the area to quell the so-called remnants of pro-Assad forces.

The massacre may be the first major one of the new Syria, but it’s just the latest in a long run of bloodletting over the past two decades. Which partly explains why Syria became the site of the largest population transfers since World War II. Today, thousands of Alawites, most apparently with Lebanese citizenship, are fleeing to Akkar’s Alawite villages and Tripoli’s Jabal Muhsin in north Lebanon. This, only months after Syrian refugees in Lebanon began to trickle back to their homes across the borders only to discover them uninhabitable.

The fledgling regime’s position is unenviable. Its orientation doesn’t do much better on that front either. Sharaa, who struggles for legitimacy and control inside Syria and recognition and relief outside it, is a “pragmatic” jihadi Salafist chaperoned in the last few years by Turkey and, more interestingly, by certain types in the British government. Syria now looks like a very tattered, sullied quilt with holes puncturing it and pieces hanging from it by the flimsiest of filaments. Sharaa means to patch it up and rule over it whole. The odds against him are close to daunting.

I say this for several reasons:

Because history teaches us so, and we human beings are notorious repeaters of it.

Because Israel is clearly intent on snatching huge swaths of the country while ensuring the rest of it remains fragmented, in line with what it would like to achieve in its would-be Levantine sphere of influence.

Because Turkey and Iran, each for their own reasons, will work very hard to derail Israel’s designs.

Because other actors, international and Arab, will fall on either side of these two camps.

Because Sharaa’s particular Islamist banner, however keen he is to project pragmatism, is neither constitutionally inclusive, nor aspirationally democratic.

Because he has to cater to his own factions, whose vision and ambition are at stark odds with those of many Syrians.

Because the state is bankrupt, US sanctions are not likely to be lifted anytime soon, and the people are desperate for safety and the most basic services on landscapes best described as shattered and dangerously chaotic.

Those who have studied Sharaa come away with similar impressions, positive and negative in equal measure. They say he is very clever, wily, and cerebral. The consummate survivor! They say his ideology is more a garb than a straightjacket. They also say he is very ruthless and power hungry with a string of brothers who were forsaken on his path from Iraq’s prisons to Damascus’ presidential palace. It strikes me that these very same attributes were ascribed to a very young Hafez Assad upon his ascension in 1970.

The Financial Times’ Raya Chalabi’s recent profile on Sharaa, which agrees with the emerging consensus, is quite revealing:

Over the years, Sharaa had gone by several aliases and titles — commander, sheikh, brother. Until recently, he had styled himself al-Fatih Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, a nom de guerre reflecting his family’s origins as well as his ambition (al-Fatih means “the conqueror”)…

He was repeatedly described to me as: “extremely bright”, “cunning”, “well-versed in regional history”, “well-read”, “a good listener” and, most frequently, “pragmatic”. But, in recent weeks, another word has begun to creep in: “strongman”.

All of which offers any number of scenarios for Sharaa and Syria, and, by extension, the rest of us Levantines. Since Syria is truly the heart of the Levant, the mother of all of us, if it struggles, we struggle with it. But only fools, at this stage, would dare proclaim with confidence the prospects of the country that used to be the jewel in the Arab crown.

We, in this region, are creatures of the chronic instabilities that append even the dullest years, of mayhem and its uncertainties. Trauma is written into practically every family’s DNA. “Recently, an international team of scientists, led by molecular biologist Rana Dajani of Jordan’s Hashemite University, published a study on the “epigenetic signatures of trauma” in three generations of Syrian families who survived the the 1982 Hama massacre and the 2011 revolt. My recommendation to them is to widen their geographic scope and calendar.”

But I’ve been asking myself in recent days: did I think that in the 20s of this century I would be experiencing what my grandparents experienced in the last one, almost to the day? Or that I would live through another version of the 1948 Nakba? Or that we would still be debating the very meaning of us?

I may have dreaded this day, but I can’t say that I saw it coming.

****

On Another Note

The recent conversation on The LRB Podcast between Adam Shatz, Rachel Shabi, and Peter Beinart on “Weaponizing Antisemitism” is one of the most enlightening I’ve had the privilege of listening to. Shabi and Beinart are the authors of two seminal books on the meaning of Jewishness and antisemitism, especially in the aftermath of October 7’s Hamas attacks against Israel and the ensuing Israeli genocide in Gaza.

If they are not already on your reading list, Beinart’s Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza, A Reckoning, and Rachel Shabi’s Off White, The Truth About Anti-Semitism, you should add them.

In the words of Shatz, the discussion in the podcast is

devoted not so much to events within the region as to their impact on Jewish communities, particularly the fierce arguments that they provoked over Jewish identity, over the relationship of Jews to Israel, over things like the definition of anti-Semitism, and over moral questions about genocide, about solidarity, about complicity.

For me, it was an education! Erudite, very sensitive, wonderfully rich in nuance, and intellectually provocative.

You must have a listen!