“And So it Was"

On Juliette Elmir Sa'adeh And Our Syrian Dreams And Nightmares Part 2

Khalil Haddad was the salt of the earth. His hometown in Lebanon was tiny Baskinta, way up north. His accent, which decades in America failed to soften, remained lovely and true to home. His demeanor was gregarious, his nature very kind and giving, his smile constant, his storytelling legendary.

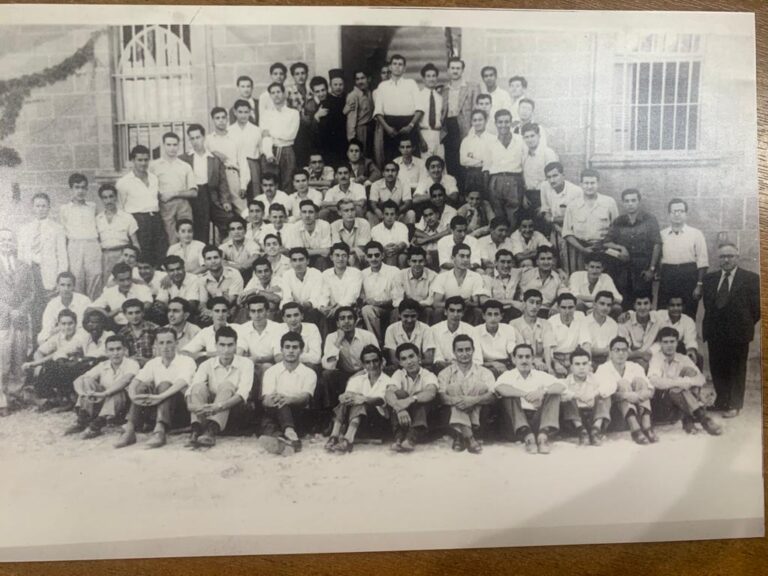

We called him Amou (uncle) Khalil, as all Arab youngsters call their male elders. But Amou Khalil, a dear friend of my father’s since their school days at International College (IC), loved us as a family uncle would, and we loved him back.

We first met Amou Khalil in Washington D.C in the late 1970s. In age, we four siblings were anywhere between very young (21) and little (10). I hovered in the middle, at 15.

From high school at Holton Arms through my undergraduate years at Georgetown University, Amou Khalil was ever present. And then life, as is often its wont, found us continents apart.

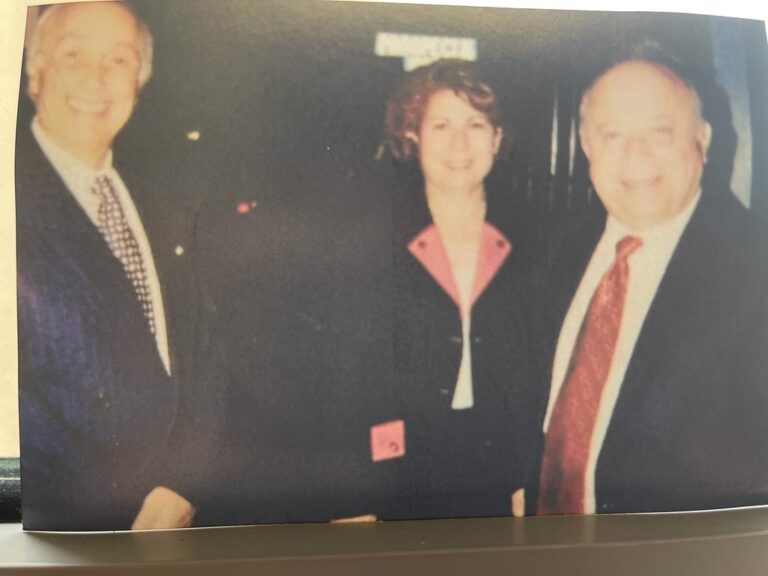

The last time I saw Amou Khalil was when I was visiting D.C in the late 1990s, well into my adulthood as a thirtysomething career woman. As we sat down to have breakfast, his eyes went misty. He passed away eight years ago, leaving behind his wonderful wife, Suhaila, and his two equally wonderful sons.

Amou Khalil had many tales to tell about his politically adventurous days in Lebanon, when he was, like my father, a member of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP). The most tragicomic of these was that one about his days in jail in Syria, where he was captured fleeing the Lebanese authorities’ wrath after the SSNP’s failed 1961 coup d’êtat.

The first night in the prison cell, they kept him standing next to a dripping faucet and under a glaring light. In the morning, the prison officer came to him and asked, “Did they feed you breakfast?” Khalil told the truth: “No, sidi (sir), they didn’t.”

“Then come let me feed you breakfast,” the officer said as he proceeded to give him a whipping.

The next morning, the same officer came back and asked him, “Did they feed you breakfast?”

Thinking himself clever, “Yes, sidi,” Khalil answered.

“And you lie too,” the officer barked. “Come let me feed you breakfast.”

I don’t know how long Amou Khalil lasted in that jail and how he ended up being released, but that story, told years later, had become a crackup. It rang agonizingly familiar; vintage Levantine hardship as parody.

The late Syrian playwright Mohammad al-Maghout was a virtuoso of such like parodies. He wove theater from the fabric of Arab life. His masterpiece, Sah al Nawm ( which doubles as good morning and hello, you get it now!), the star Syrian series of the 1970s, was perhaps his most brilliant depiction of us. Amou Khalil’s days in the Syrian prison’s hospitality could have easily been an episode in Sah al Nawm.

So could many scenes in Juliette Elmir Sa’adeh’s memoir.

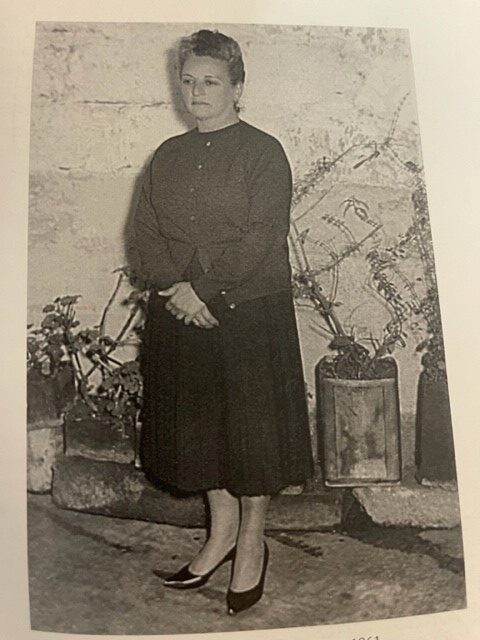

Juliette was imprisoned twice between 1949 and 1963, when she was finally released to live her life quietly. The first one was in 1949 as a confinement of a sort in the Saidnaya Monastery near Damascus. The second commenced with incarceration in the notorious Mazzeh prison, when the party’s leadership was implicated in the 1955 assassination of Adnan al-Malki, the Syrian army’s deputy chief-of-staff (see part 1).

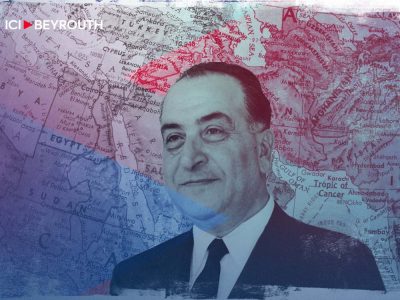

She was devoted to the SSNP and its ideology, but she was more a confidant of her husband’s than a political operative in her own right before his execution in 1949, and she was never privy to the weird machinations and conspiracies of the ever so strange George Abd al-Massih, who became head of the party upon Antoun Sa’adeh’s demise. And yet, she would become the first female political prisoner in the Arab world.

Unlike Amou Khalil and scores of other party members who were tortured in Syrian and Lebanese prisons with extraordinary violence, especially after 1961 coup, Juliette was never physically mistreated, but the psychological torment and solitary confinement were their own kind of hell. Those Lebanese who pine for President Fouad Chehab’s (1958-1964) golden age are in fact indulging in another one of their delusions about the unfettered glories of the distant past.

Juliette didn’t take it quietly. She would scream and lash out and protest and stop eating and refuse to communicate. But of course, her prison years were rich material for al-Maghout’s pen.

One such moment, in the late 1950s, the warden “directed the policeman, in my presence, to shoot me if he saw me attempt to throw myself from the balcony.” I don’t know if Juliette was laughing when she wrote these words, but there isn’t a Levantine soul who would not be in stitches and nodding at reading them.

Soon after that incident, Juliette was transferred to al-Qal’a prison in the heart of Damascus, where life takes on a different mood in that big, open room the prisoners shared. She becomes the wise one there, to whom many would go to seek advice or vent. She had that kind of charisma.

And soon after that, news reaches her of the 1961 coup, which took place as December 31 gave way to the 1st of January, and failed right then and there. She writes, “How strange was that news, which caused me much pain! A failed coup, and in Lebanon? What now after this failure?”

That was the mystifying thing about the SSNP: a supposed revolution in 1949 that died two days after being launched, and a 1961 coup that failed barely hours into the attempt. In both cases, the gap between what the leadership thought it could do and what it was actually capable of achieving was painfully glaring. The price paid by the party and its cadre would be backbreaking.

For Amou Khalil, for my father, and for so many other SSNP members, there was life before the coup and life after it. They scattered across continents, some to the US, some to Australia, some to Africa and Latin America, and others, like my family, to Jordan. Most remained true to the ideology, but far fewer, I suspect, to the party itself.

****

On Another Note

It feels, everywhere, like the last chapter, doesn’t it? Personal tragedies, national calamities, international crises. This is a year, a season, a time that appears very miserly with its mercies.

“Our age is badly in need of a strong dose of creative, revitalized Epicureanism,” Robert Harrison writes in the London Review of Books. “For Epicurus offers us a philosophy of how people can, on their own initiative, create little wellsprings of happiness in the midst of the wasteland.”

I think it’s the moment to become Epicurean.

As usual, if you are not a subscriber and would like to have the full piece, I am happy to gift it to you.