Between France’s Burkini and Lebanon’s Bikini

You will remember, perhaps, that incident in 2016, when the French police asked a Burkinied (add this nifty new word to your dictionary) woman on a beach in Nice, in the South of France, to remove her garb. Around the same time, another hijabed woman on the shores of Cannes was fined for a dress code that does not “[respect] good morals and secularism.” The jeering crowd in Cannes weighed in with “go home.” She was a French Muslim.

Last week, on a public beach in Sidon, in South Lebanon, two presumed Sheikhs went after a man and his wife. Their issue was the woman’s swimsuit, which violated “good morals and Islam.” A few days later, as feminist activists, women and men, gathered near that spot to protest the harassment of the couple, a counterprotest pushed back. A veiled lady told one of the female protestors, “You can’t wear a bathing suit in Sidon. We are a conservative society. Go wear it somewhere else.”

There is something to be said for bigotries that transcend geographies and cultures and political systems. These specific ones on French and Sidonese seafronts are wonderful in the way they highlight that gnarly matter of freedom of choice and the bluffs it calls in people that think themselves democratic, free, and be and let be.

Generally speaking, in France, a run-of-the-mill liberal democracy, you can’t go around completely naked. But in certain regions and places, private and public, you can pretty much parade close to bare or with the skimpiest of fabrics.

In Lebanon, whose so-called democracy is just one of the many delusions we Lebanese like to latch on to, the personal status laws are extremely unforgiving towards us women but the social mores are quite flexible, depending on location, social profile, and sect. Within a certain radius in public Beirut and on private beaches everywhere, a woman can pretty much wear whatever she wants. Not so, say, in the wide open outdoors of Sidon and Tripoli, Lebanon’s second and third largest coastal cities.

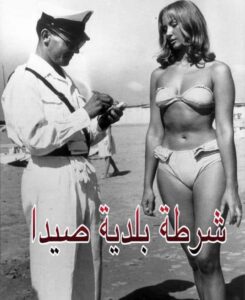

This, mind you, wasn’t always the case, contrary to what that miffed Sidonese woman said. Once upon a time not long ago, in the 1960s and ‘70s, girls would cross the street from their home to the public beach as they were stripping down to their bikinis. I can safely say the same for countless Arab locales which frown upon such sights now.

There is nothing immutable about intolerance, nor about freedom, and both have the habit of moving in every direction. When the pendulum swings back, its first victim is almost always the other. In this push and pull, the Sheikhs’ reaction, frankly, is much less interesting and unnerving than the French one. Theirs is but one extreme expression of beleaguered societies that are continually struggling with modernity and its rights and liberties. The French reaction is what? One would think that the modern sense of self is confident enough to be at least indifferent towards people’s freedom to choose, however unappealing or offensive the choice.

We happen to be talking here about the burkini versus the bikini. But you can pick your way through the countless objections erupting everywhere in the world: against womanhood itself, homosexuality, the colors black, brown, and yellow, them and they, migrants, Muslims, Christians, Shiites, Sunnis…

Whether we are born with it or we opt for it, otherness is, perhaps, the ultimate benchmark of humanity’s tolerance towards those whose identity, for whatever reason, deliberately or not, stands out in a sea of relative sameness. It is telling that liberalism begins to flounder when homogeneity appears to be losing its edge.

The truth is othering is one of our favorite pursuits as human beings, and the cruelest. That we play it so well in the Arab world, where religion and patriarchy and autocracy come together to reduce many a vulnerable person’s universe into an excruciatingly lonely place, is at once predictable and tragic. But there is a truth no less compelling in what we witness in countries whose legal norms and political culture had supposedly evolved to respect and protect their citizens’ freedom of choice.

Not so, we are learning time and again.

Meanwhile, It’s been reassuring to know that Lebanese humor has emerged intact from yet another controversy, which are a dime a dozen these days.

****

On Another Note

The Quietism of Montaigne has always had an admirer in me, perhaps even a subscriber. I read him a long time ago, and found my admiration for him rekindled by Tobias Gregory’s review of Philippe Desan’s Montaigne: A life. Here’s an excerpt:

Montaigne insists on the veracity of his self-portrait. He writes, he declares, just the way he talks. To keep his book true to himself he will correct only the careless errors, not the habitual ones, so that ‘everyone recognises me in my book and my book in me.’ In a passage added late in life, he describes the effects of continuing self-description: ‘By portraying myself for others I have portrayed my own self within me in clearer colours than I possessed at first. I have not made my book any more than it has made me – a book of one substance with its author, proper to me and a limb of my life.’

As usual, if you’re not a subscriber to the LRB, I am happy to gift the piece to you.