“In Search of Fathers” Part 1

I was barely into the first few pages of Raja Shehadeh’s We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I, when a 24-year-old inscription rushed back to mind.

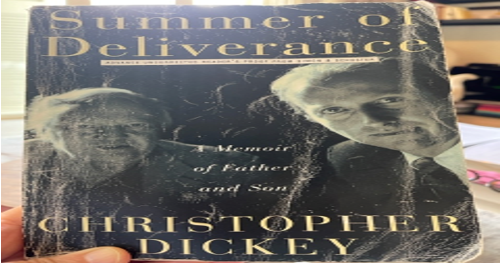

In 1998, my friend Christopher Dickey (1951-2020), an author and then Newsweek’s Middle East Editor, came visiting in Beirut, bearing with him the advance uncorrected reader’s proof of Summer of Deliverance. Chris was the son of the very famous (and no less infamous) James Dickey, the poet and novelist. The bestseller Deliverance, which came out in 1970, was his debut novel.

Chris inscribed his book before we went for lunch and handed it to me. “In search of fathers,” he wrote. When I read it, I immediately looked up and found him smiling. That was the thing about Dickey: seemingly effortless insights that almost always approached wisdom.

So it is with Shehadeh, a writer himself and perhaps the most prominent human rights lawyer in the Occupied Territories, who disentangles the history of a family, of a father and son’s complicated relationship, of Palestine and its century-old struggles, in prose so clear and disciplined you find yourself moving with such ease through reams of facts and emotions.

Like a fellow traveler, you trek with Shehadeh through a story laden with questions and lament, with confessions and conjectures, with arguments and revelations. You catch yourself underlining passages that recall your own disquietudes, marking doubts that echo yours, walking through emotional terrains excruciatingly similar to your own, even though you, the reader, are in the end no more than a voyeur.

Two tragedies guide Shehadeh’s memoir: the murder of his father, Aziz, in 1985, and Palestine. From these, he painstakingly distills the myriad sufferings that each has unleashed on person, family, and people. Aziz was a giant of a man, a visionary, an extraordinary legal mind, and a tenacious fighter for his kin and cause. In the early 1980s, when his son Samer and I met and became friends as students in Washington D.C, Aziz was already known to me as a leading Palestinian figure in the territories, famous for his epic court wins and relentless pursuit of an independent Palestinian state.

Long before the two-state solution became the bedrock of international diplomacy on the Israel-Palestine debacle, it was Aziz’s, with infinitely better conditions for the Palestinians. Long before Palestine’s advocates understood international law as a potent weapon against Israel’s transgressions, it was Aziz’s. He lived and died a very lonely warrior, but it’s not his politics that got him killed. Even though Israel has yet to relent and release the file on the investigation to Raja, it’s a near certainty now that Aziz was murdered by the defendant in one of his court cases. Absent the file, it took Raja decades of hard work to arrive at this determination, but apparently no more than a few weeks for the Israeli police themselves.

On the face of it, it might seem curious that the Israelis would choose to sit tight and keep mum about a murder case, but to all those who have experienced the method of its occupation, this is vintage Israeli behavior. It no doubt gave them great satisfaction that the unfounded rumor that Aziz was assassinated by a raging Palestinian diehard grew into a conviction.

It’s the long-neglected archive of meticulously maintained papers and notes, which Raja finally sits down to read three decades after his father’s death, that reveal the minutiae of Aziz’s history with the Palestinian cause and the enormous toll it took on him. At the end of a stream of very painful and precious discoveries about the man, about the ordeals he suffered in silence, about the similarities in the legal and political quests of the two Shehadeh men, does Raja come to the heart wrenching conclusion that “we could have been friends, my father and I.”

At one point, after one such discovery, Raja asks, “ How is it that I remember none of this? How is it that his unjust imprisonment [by the Jordanian authorities] under such harsh conditions didn’t make father a hero in my eyes?” Well now he is in Raja’s–and, indeed, in ours.

This post is the first of several on “In Search of Fathers.” I have so much more I want to say about Raja Shehadeh’s memoir, about Palestine, and about sons and daughters’ conversations with long gone fathers.

But if I have a wish for my readers at the end of 2022, it is to read We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I. You will be all the richer and wiser for it.

****

On Another Note

Today, the World Cup comes to an end. It’s been a peculiar one, especially for many in colonized sphere. It’s certainly been a charged one for us Arabs: we have watched Qatar attacked and vilified in ways that, at times, have gone way beyond legitimate criticism, smacking of ill-concealed Western hypocrisy and racism, all while basking in the Moroccan team’s wins. That the Palestinian flag became the object of love and center of attention in and outside the stadium only added to the excitements of the past two weeks.

Explaining it all is an outstanding piece by Brahim El Guabli and Aomar Boum on the myriad meanings of the Moroccan team’s success at the World Cup:

The world has discovered Morocco’s pan-nationalism, pan-Africanism, pan-Arabism, its fluid citizenry, its deep Amazighity, its values of motherhood, and its players’ engagement with complex issues in ways that made history. Some of the games Morocco played and won also have a historical charge, particularly in regards to the legacies of Muslim Spain (Al-Andalus), Reconquista and colonialism in Africa and beyond. Morocco’s victories have rubbed French nationalists the wrong way, and a senator from Marseille has demanded that Moroccan flags be banned during the match opposing Morocco to France… While football is and remains the determinant of the winner, the broader ramifications of a game extend far beyond the space of the stadium, allowing us to see football, in key moments, as a space for cultural pedagogy and historical conscientization.