“In Search of Fathers” Part 2

On Raja Shehadeh’s We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I

An afternoon in 1972, a quiet conversation between two old Palestinian warriors in a living room filled with books. The two had not seen each other in decades, one presumes. Once protagonists on behalf of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees, now they fidgeted awkwardly in their seats as they chatted.

They had much in common, but between them were all the usual barriers of life and its traumas. Two very capable, even brilliant lawyers, they had failed in their larger mission of winning for their people the right of return in the immediate aftermath of the 1948 war. International law was with them, the UN as well, but the region’s geopolitics was just not amenable.

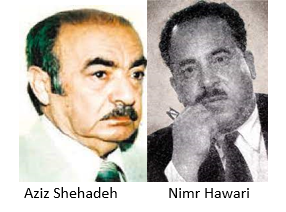

The gentlemen are Nimr Hawari and Aziz Shehadeh, Raja’s father. The setting is Nimr’s home in Nazareth, five years after the Arab-Israeli war and the loss of the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Raja, who accompanied his father on that visit, was just 21 years old. He sat listening and, as the memoir shows, registering every detail of the back and forth.

What Nimr and Aziz share on that day is a distillation of the Palestinian predicament: the hardship it caused to those who stayed, those who were expelled or fled, and those few who were able to return; the estrangements it created between them; the separations it imposed; the encirclements it exposed, and the enfeeblements it fed, leaving a defeated people unmoored and unbearably alone.

During one of their visits to Lausanne in 1949 to push for a solution as founding members of the Arab Refugee Congress, Nimr and Aziz were made an offer by a very cynical Eliahu Sasson, a member of the Israeli delegation. The Israelis flatly rejected every proposal for return made by the two, but Sasson extended an offer to them to return to their own homes in Nazareth and Jaffa (Haifa). Nimr took him up on his offer, Aziz didn’t. He set up a new home in the West Bank, only for it to be conquered and occupied by Israel in 1967.

The conversation stripped to its barebones:

Aziz: “I am curious to know. What made you decide to take up Sasson’s offer and go back?”

Nimr: “I considered very carefully all my options, Arab country after Arab country, but decided that none was suitable for me to work for the welfare of the refugees in them. So I thought that now that this battle is over I might as well take up the offer of the Jews to return to Israel. And that’s what I did.”

Aziz: “What was it like to return?”

Nimr: “At first I was accepted by neither the local Palestinian population, who were as miserable as can be, nor the Jews, who were flushed with victory and regarded me with derision, as if they had done me a favor for which I should be forever grateful by allowing me to return to my country. Of course, they didn’t recognize that it was my country, they believed it had become theirs and only theirs.”

Aziz: “Did you settle immediately in Nazareth?”

Nimr: “No in the beginning I lived in Akka, where I met with a lot of opposition from the communists… In their newspapers they wrote that ‘the Israeli authorities brought Hawari back while they pursue those who returned to Haifa….’ As if any of this was my fault and I should feel ashamed of returning home… The communists held on to my return as proof that I was a collaborator with the Jews…”

Aziz: “Did you regret your decision to go back?”

Nimr: “But what’s the use of regretting?…I was exhausted. I wanted to go back home even when I was aware it would not be easy to live under Israeli rule…. I moved away from politics and concentrated on my legal practice, taking cases to the High Court of Justice including that of the two Christian villages of Kafr Bi’rim and Iqrit.”

Aziz had not known about this case, so Nimr went on to explain that these two villages had not taken up arms during the war and were promised by the Israeli army that they would be evacuated only for two weeks while the army wrap up its operations. The army then reneged on its promise. Nimr won the case for the two villages in Israel’s High Court of Justice, but the Israeli army refused to comply with the judgement.

It was Nimr’s turn to ask. “What about your political involvement?”

Aziz: “In the early 1950s we believed the Jordanian regime would give us the opportunity to take part in the government and influence the politics of the country… For all these past nineteen years we felt repressed, imprisoned…After the occupation much more became clear to me. I had been deluded, like others, about the power of the Arab states and their ability to win the war with Israel. When I put all I knew together… I arrived at the conclusion that we must call for peace with Israel and achieve self-determination through our own Palestinian state.

Nimr: “But you’ll not succeed. Israel will never agree to a Palestinian state, Never. What you’re calling for is not feasible.”

Aziz: “And I thought you might be an ally.”

Nimr: “Let me warn you about what to expect, I can do this because by now I know the ways of Israel.”

It’s the futility of it all that struck this reader hardest by the end of the visit. The Palestinian catastrophe was laid out in all its tragic regalia. Like other such encounters reconstructed by Shehadeh, the conversation illuminates the myriad discords that spawned in the shadow of one epic, unending conflict. And of all the discords that permeate the memoir, it’s that hushed one between Shehadeh and his father that resonates the most. Unbeknownst to either, they were kindred spirits all long, down to their signature. When Shehadeh started reading Aziz’s archives decades after his murder in 1985, he noticed that he signed his papers as Samed, “that who perseveres.” And that who stands his ground. Exactly the same signature the son had always used in signing his.

Alas, a very lonely happy ending.

****

On Another Note

It’s the dawn of 2023. Here’s Robert Harrison in Entitled Opinions, with three poems for the Winter Solstice.the