“And So it Was”

On Juliette Elmir Saa'deh & her Syrian Dreams and Nightmares Part 1

The time between World War I and World War II! Those jaded photos and silent reels of faces and places, of grand political drama and commonfolk going about their daily routine. The stuff of life encountered in memoirs and letters and diaries against a backdrop of ominous happenings.

It’s all such riveting historical theater to me.

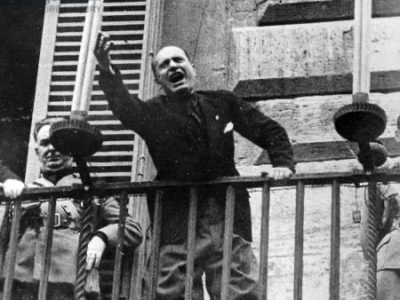

Black Shirts parading, Il Duce having fun with the crowds from his balcony; Hitler’s armies marching, saluting the horrors unfolding; him in his Bavarian retreat playing with his German Shepperd Blondi; pedestrians crossing busy Parisian streets, gals giggling by the sea… The epic and ordinary, the tragic and the farcical, sharing the hours of the day, the days of the week, always together, as if siblings.

Recently, I read Jenny Uglow’s review of Caroline Moorehead’s Mussolini’s Daughter: The Most Dangerous Woman in Europe in the New York Review of Books. It made my morning. The book is already on my reading list.

I am fascinated with that same pocket of Arab history. But such is our Arab life, the period reaches much closer to the late 1960s. It’s a thing of mine, a fetish if you like: the details of that world, its fleeting moments and major events, its moods and rhythms, its big characters and their idiosyncrasies.

So, I just finished the memoir of Juliette Elmir Saa’deh, the wife of Antoun Saa’deh, the founder of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party. I have just begun researching my father, Ali, and so I started to research the SSNP. Between the age of 16 and 30, it shaped his politics and much of his worldview. In 1961, it almost got him killed.

Why I’ve gone this far knowing little about the party’s chronicles is another story. But, as I began, I suspected that Juliette’s memoir would offer me the intimate glimpse I’m forever searching for. What better introduction to those crucial early decades than her pen? By the end of the book, I was happy I chose well.

I approached the memoir free of any notions about Juliette bar those impressions that I had picked up through the years from my parents’ brief conversations about her. They thought her very kind, gentle, and decent, and so I did too. They spoke of her endless suffering after Saa’deh’s summary execution in 1949 by the Lebanese authorities, those long years of unwarranted imprisonment in Syria and that stifling existence, in between and after, accommodating the onerous commands of the SSNP’s grandees. They believed themselves guardians of the al-amina al-oula (the first trustee), as she was called, and her three young girls. They were almost always idiotic and unbearably intrusive; she was almost always choked but ultimately amenable.

Ironically, although she was never more than the aggrieved young widow of a failed revolutionary, she ended up spending more time in prison than many of those grandees themselves.

This much I knew, and this much she narrates in detail. What forms gradually is a very interesting portrait of a woman who spends the better part of her political and personal widowhood navigating a treacherous Arab life. As the years go by, the distance between her conviction that the party, to which she was wholly committed, shall in the end triumph, and her candid revelations about the apathies and “madness” within, becomes glaring–and of course, tragic.

But what emerges as well is an intriguing sketch of Antoun Saa’deh himself. Juliette renders a revolutionary with a very soft heart; an intellectual with little insight into the character of people, a revered leader whose word, to his men, strangely, was never final; a very loving and playful father who insisted his daughters speak in formal Arabic; a husband whose tenderness suffused every gesture towards his wife. All the more peculiar then that Juliette never once addresses him by any name but “the leader,” (al zaim), as has the party cadre long before and after he fell.

If you are not familiar with the SSNP, you will be asking by now what it stood for. That’s for another post. My interest here is the human angle, not the politics.

I asked my mother about Juliette two weeks ago. She remembers clearly the first time they met was in Paris sometime after 1963. My parents went to visit her in the apartment of her middle daughter, Elyssar, and her husband, where Juliette lived for a while when she was finally released from her Syrian jail after an eight-year incarceration.

And that, as it happens, is where the memoir ends. But it is on the way there that Juliette, perhaps without ever meaning to, offers clues about why a party with such serious ambition and ideological appeal would always be so susceptible to the tragic and comic. In that, it was not alone, it is true. And therein lies a fascinating story well worth a ream of intimate histories.

Two very brief conversations in the memoir are revelatory: the first between Juliette and Saa’deh on July 2, 1949, one day before the SSNP declares a revolution in Lebanon; the second in Damascus, in 1955, between Juliette and George Abd al Massih, President of the SSNP.

July 2, 1949:

Juliette: Are you one hundred percent sure that the revolution will succeed?”

Saa’deh: “I am not even fifty percent sure.”

Juliette: “Why take the risk then?”

Saa’deh: “ I wrote to our comrades to that end. I informed them that the Syrian government had broken its promises to us. Their answer was that they would not backdown. They stated that they would continue with the revolution, even if I gave the order to postpone it.”

July 5th, 1949, the revolution is declared a failure. Saa’deh is executed on July 8, 1949.

1955:

Juliette shares with Abd al-Massih her conversation with Saa’deh.

Abd al-Massih: “I am the one responsible for those words… the revolution was declared and we had to follow through with it.”

Juliette: “How could you say this to the leader, when you were the one who told me that the nationalists were not ready for this battle? You insisted to the leader that you had more than seventy men at the ready, while in fact you had found it difficult to rally seventeen men. The reality of the situation was that you had twelve men. How could you press the leader to proceed with such meagre numbers, and have him take responsibility for the failure of the revolution?”

Abd al-Massih yells back: “ Do you think it was possible to avoid the revolution?”

His habit was to connive, yell, and brood. “Grinding his teeth violently” whenever he was confronted or challenged was another pastime of his.

Shortly after their conversation, Juliette is arrested as a co-conspirator in the murder of Adnan al-Malki, the deputy chief of staff of the Syrian army. Abd al-Massih, the actual co-conspirator in the murder, manages to escape, of course. She ends up in Syria’s infamous Mazzeh prison.

There, aggrieved and confused, she once erupts at ‘Izzat Hussein, the prison’s warden.

“Why am I being treated in this manner? I don’t know what has become of my girls, and I don’t know why I am in prison,” she pleads.

In a reply for the ages, Hussein reassuringly offers her this: “It is alright, they will be raised as both orphan Jesus and orphan Mohammad were raised.”

Laugh and cry?, I ask myself. Yes, do both.

****

On Another Note

And here’s an excerpt from Uglow’s review of Moorehood’s book on Edda:

A tall, rangy teenager, Edda shared her father’s disconcerting stare. Praised by the press for her “grace and charm,” in reality, Moorehead tells us, she was “awkward, prickly and combative,” hiding her intelligence and skills. Mussolini let her cycle, swim, and wear trousers, but not smoke or go to dances. In 1929, when police reports arrived of the “fortune hunters, spendthrifts and drug addicts” who pursued her during family summers at Riccione on the Adriatic and of her own “apparent allergy…to suitable young men,” he packed her off on a long cruise to India to “tame” her.

Fascinating! If you don’t subscribe to NYRB and would like the full piece, I would be happy to gift it to you.