Lebanon’s Golden Age through A Different Lens

Not every reference to a country’s golden age implies a current one made out of muck.

In Lebanon, it does. Almost always when Lebanese are referring to the country’s golden age, they mean to juxtapose it against today’s dark one.

There is the broken, bankrupt, corrupt, soiled, pervasively sectarian Lebanon that we have now. And there is the Lebanon that was once the jewel in the Levantine crown.

That moment of zenith, in the mind of those Lebanese who hark for it, stretches from, let’s say, the late 1940s all the way to the late 1960s. And it is usually told through visuals.

We have elegant and beautiful Lebanon, like one of its presidents and his wife, Camille Chamoun (1952-1958) and Zelfa.

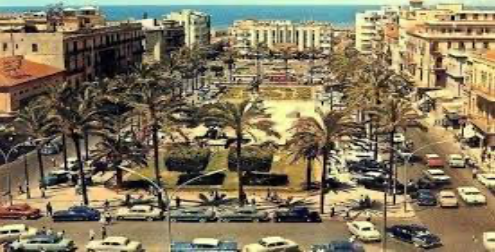

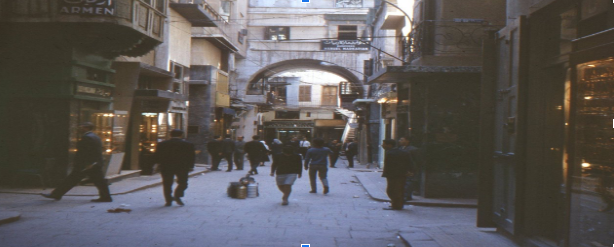

We have the Lebanon of the immaculate Martyr Square in the center of town and the ancient souqs that gave the modern metropolis its eastern texture and verve.

Also the Lebanon of St. Simon by the sea, the ski slopes of Farayya, the Baalbak Festival, the intellectualism of the Horse Shoe Café, the zing of the Cave du Roi, the bling of Hamra Street.

The lush mountains, the terraced villages, and the magnificent cities of Tripoli and Sidon are part of that album as well.

And what these visuals come together to convey is, of course, Lebanon’s golden age. It’s not to say that Lebanon then was perfect, but that it’s imperfections were infinitely less malignant than this one’s. If you were to convey the attitude in three words, it would be bas mish heik: but not like this.

You hear it often: it was not like this in the 1950s and ‘60s. There was sectarianism but not like this. Politics was dirty but not like this. There was corruption but not like this. The judiciary was compromised but not like this. The laws were broken but not like this.

To be fair, these bas mish heiks wouldn’t work without the positives that give them their vim: economic prosperity for long periods of time, thriving middle class, financial hub, rambunctious press, cultural attractions, playground, the extraordinary flair of Beirut…

On the surface, where most impressions dwell, it’s all accurate just about enough to give the ring of truth to the proposition that the old Lebanon was quite well.

But Lebanon was never well. Its golden age was simply that of an experiment in its early stage. The structural malformations that entrenched frictions and practices that celebrated blithe excess were just beginning to mold the state and the shape of its politics and economy. Lebanon looked kind of well because it was not yet that glaringly ill.

I sound cheeky but don’t mean to be. In fact, there was time and opportunity in those early decades to mend the utter madness of this place had its caretakers cared enough to do so. But they didn’t. Not because they couldn’t, or because the world wouldn’t let them, but because they didn’t want to.

And they didn’t want to because they loved Lebanon just the way it was. The sectarianism suited them, the state’s feebleness suited them, and they wouldn’t let go of its laissez fair, devil-may-care, monopolistic, import-based economy even if you put a gun to their head and pulled the trigger. Which we know has already happened more than once. They knew that this model of rule ordained the failure of Lebanon, but it didn’t really matter to them. And they knew because forewarnings of its doom accompanied the celebrations of its birth.

So, if we are genuinely keen on identifying the culprits in the failure of this experiment 100 years after its first iteration by the French and their Lebanese devotees, cherchez l’élite.

But what’s really interesting in this story is this ever evolving and yet unchangeable consortium of bigwigs.

When the country became independent in 1943, around 30 families reigned over it, if we are to take Fawwaz Traboulsi’s estimates in his The Social Classes and Political Authority in Lebanon (2016). Twenty-four were Christian, four were Sunni, one was Shiite, and one was Druze. The members of this tiny club were mostly mercantilists sharing between them the country’s import monopolies and everything else in between. You name it, they owned it: land, real estate, banks, ports, hotels, tobacco concessions, construction, insurance companies… They would have politicians in the family, alliances with other powerhouses through marriage or business partnerships, very close ties to foreign interests, and their favorite sectarian parties, feudal bosses, and small-time politicos to support in national and local elections.

Over the years, this club of magnates would necessarily change and grow to include a richer variety of cross-sectarian wealth. By the 1960s, members grew to an estimated 100 families, reaching upward of 800 by the early ‘70s.

Immigration, economic trends, war; they all played their part in breaking lose the locks on the gate. When the 15-year civil war ended in 1991, the consortium enjoyed its biggest expansion to include a new breed of elite: warlords and heads of militias who had amassed enormous power and were ready to cash in. It would also boast carpet baggers from all walks of life, security apparatus grandees, and a new class of billionaires, like the late prime minister Rafiq Hariri. In 2013, according to Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Data Report, 8900 individuals owned 48% of Lebanon’s resources.

But here’s the thing: remarkably, these arrivistes, whose very grievance was the old elite and their Lebanon, came in, wore that ring, put on that robe, felt that shudder, and proceeded to do what their predecessors had always done: nothing. They protected Lebanon as is, and not only that; they introduced innovations that entrenched its worst political and economic features and tickled its most horrendous demons.

And so what we in fact had over the course of 70 years is an elite that expanded in numbers, in backgrounds, in sects, in political orientation, in the source of wealth and its production, whose behavior towards the country never altered.

Those leaders who prostrated themselves to Ghazi Kanaan, Syria’s viceroy in Lebanon post-1991, were simply following in the footsteps of Bechara al Khoury (1943-1958), the first president of Lebanon. Per the French archives, in lobbying for the position, Monsieur Khoury prostrated himself before General George Catroux, the General Delegate of Free France in the Levant.

The 1975-1990 civil war was the sequel of the 1958 strife.

The quotas that allocate every position in government per sect are based on the same method that did so in the 1940s.

The debt-fueled, import-anchored, aid-greased, consumption-obsessed, neoliberal economy that has defined post-war Lebanon is little more than an unvarnished and cruder copy of the one that underwrote the pre-war one.

Election rigging, vote buying, and the blatant interference of the security services that have marred every election since 1991, did so to every election before it.

The mammoth corruption that afflicts every corner of the state and its economy, a Haririan legacy par excellence, was always there but on a smaller scale.

The current security apparatus is a more sophisticated and elaborate version of the one President Fouad Chehab (1958-1964) built and unleashed on his people.

This is all courtesy of a ruling class that kept changing in profile and names and size but never in its behavior towards the Lebanon over which it has reigned.

And here we all are in this swamp, not because the new guard betrayed the Lebanon of the golden age, but because they held on to it for dear life.

They looked like that in the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s because it was the beginning of the experiment. We look like this in 2023 because we are at the very end of it.

****

On Another Note

This is a very critical moment for Israel; more so for the Palestinians. Recently, several highly respected and astute observers of the Palestinian-Israeli scene warned that a Nakba, mass expulsion of Palestinians similar to 1948’s, is possible and perhaps even near.

We all know Peter Beinart. He has emerged as an extraordinarily influential and eloquent Jewish-American defender of Palestinian rights. In this masterful piece in Jewish Currents, he explains how ethnic cleansing has been central to Zionism and argues that another Nakba could happen in the Occupied Territories.

In his influential book, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, the Israeli historian Benny Morris writes that in the 1920s and 1930s, as it became clear that Arabs would resist Jewish sovereignty and the British would sooner or later restrict Jewish immigration, “a consensus or near-consensus formed among the Zionist leaders around the idea of transfer as the natural, efficient and even moral solution to the demographic dilemma.” In 1938, David Ben-Gurion, who would become Israel’s first prime minister, declared, “I support compulsory transfer.” The following year his chief rival, revisionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky, concurred that “the Arabs must make room for the Jews in Eretz Israel. If it was possible to transfer the Baltic peoples it is also possible to move the Palestinian Arabs.”