Letters Between Friends: Part Two

In this post, I shall meander simply because I want to.

My first time in Cairo was in 1974. On the drive from the airport to the hotel, I remember looking out of the window and thinking to myself, I’ve been here before. Home!

It was a typical family vacation, visits to the new and old, a taste of culture, a peek into local rhythms, interspersed with sibling repartee and fights. My sister Raghida was approaching her 17th birthday and about to go into full bloom; my brother Fadi and I were the agitated teenagers in the middle; and Iman, five years younger than me and the last, at six, was a sweet, delicate thing.

It’s true that Cairo has changed over the past 50 years. It’s also true that it hasn’t. It’s still a hoary, hypnotic city, crowded and loud, so very tired and yet so very alive, sultry and hard, lush and dusty, flirtatious and dead serious, with gray permanently coating its tree leaves and skies.

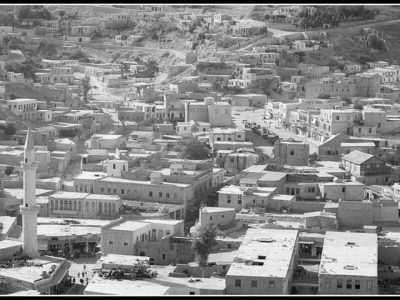

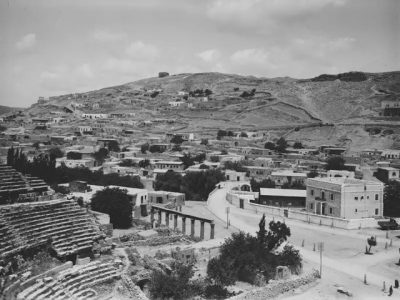

When I first visited, there couldn’t have been a sharper contrast between two Arab cities than between Cairo and Amman. At that time, Ammanis were no more than 475,000, Cairenes 5.5 million. They had the Nile, we had Aqaba, three hours away by car, on the Red Sea. Cairo hustled and bustled, we maundered and purred. On a clear day in Amman, and they were many, you could see where the horizon and earth meet. Our circle of life was a few minutes away in any direction. In Cairo, you had to ride the Nile to set your eyes free, and you felt as if that city could go on for an eternity.

I became a regular visitor to Egypt since that first encounter. In 1992, I even thought of making a documentary on the “mou’alimat,” female patrona who presided, much like old-style tough guys, over sundry traditional trades and neighborhoods. They used to feature all the time in old Egyptian movies but had become a fading quirk of the country’s fast-changing urbanities. I accompanied my friend and relative Hanan al Shaykh, the novelist, who was invited to lecture at Cairo’s literary atelier. As her daughter Juman and I sat, along with Egypt’s literati, in the cozy space listening to Hanan and the Egyptian writer Edward Kharat musing about prose and literature, Cairo’s distinct scents and pollutions wafted through the tiny window. In Cairo, life sang through such intimate frictions, all intense and wonderful.

Christopher Dickey, a dear friend, was Newsweek’s Cairo bureau chief at the time. So, our one-week stay ended up as a total immersion, with excursions to artists studios’, Chris’s Zamalek apartment, the old meat market, the Hussein Mosque, the Fishawi Café, Midaq Alley, City of the Dead, and the garden of the Marriott Hotel.

I lived Cairo the way a daughter of hers would. It all felt deeply familiar: good habits and bad, the dos and don’ts, the unwritten rules that guide relationships between the rich and poor, the thinkers and the money makers, the open spaces and the no-go zones. Nothing came out of the documentary project, though.

In her recent letter to me, my best friend Joye recalls “the evening smell of burnt corn husks,” that filled Cairene air.

We were perplexed coming home from dinner every evening to find all manner of family groups picnicking on the traffic islands well into the night. I’ve never felt so safe in a multitude. Every evening, they came out in droves and repossessed their Pyramids with picnics. They lounged upon the rocks. These stones were theirs and they played over them as if the two-ton plinths were beloved children that they’d shared with the world for a time and then took back.

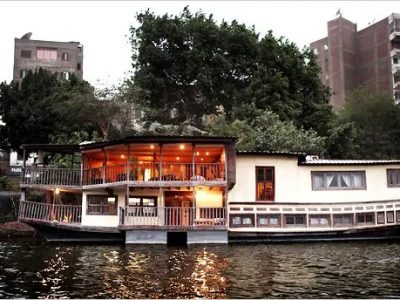

I haven’t been to Cairo since 2014. It’s 10 million people today and counting. A changed city, I hear from friends. A changed Tahrir Square. A changed Nile scene, now all but emptied of its legendary houseboats, those enchanting Feluccas that dressed the river’s banks.

The last time I was in Amman, a couple of months ago, we got lost on the way home from dinner at a friend’s in Dabouq. It was dark, we thought we missed a turn, and the GPS kept playing tricks on us. It took half an hour to regain our footing, but throughout, we were actually four minutes away from our house. When I first realized this, I was stumped, and then I fell silent.

It’s not only beauty that silences, I wrote to Joye in my reply.

Amman’s population size today, at 4.5 million, is close to Cairo’s in the early ‘70s. When Abd al Rahman Munif, the author, was growing up there in the mid-1940s, it was a tiny town of around 43,000. How utterly lost he would be in Amman now. Like me.

It wasn’t natural population growth by any stretch. Jordan was perhaps foreordained to be a sanctuary for people fleeing the horrors of their own countries. My family did in 1962. For my father, a man condemned to death in absentia, Jordan was deliverance. But so many, in successive waves from Palestine and Iraq, from Kuwait and Syria, have settled in the Kingdom since 1948.

We ourselves fled Lebanon, a country that had long been a haven for escapees from somewhere else, an extraordinary mélange of refugees living in squalor, intellectuals inhabiting Beirut’s cafés, dissidents fleeing their masters’ prisons and guillotines. It all depended on one’s circumstance and politics. It still does to a large degree.

Beirut in 1950 was an estimated 322,000, in a country of 1.5 million. Today, we are 2.5 million, representing 40% of the population. Ever since 1948, we have been obsessing about the Palestinians in our midst, now fewer than 240,000. Then Syrians began to seek refuge in 2011, reaching an estimated 2.2 million. Even if every Syrian were able to return to Syria eventually–which we know is not going to be the case for a good majority–it would be decades into the future at maximum absorption rates.

Meanwhile, many Lebanese have packed and left. Accurate figures are hard to come by, but if the oft quoted range (220,000-270,000) is reliable, then 4 to 6% of the population, mostly young, educated, and talented, are gone.

This is a Levantine story with deep roots in history. And the effect of such inflows and outflows of people on our modern identity is rich in pain and blessings. So, we expect these latest tectonic trends to yield their own imprints. Cities are the seedbeds of renewal, innovation, and creativity. They grow and transform and respond to those who inhabit them. They are what we will them to be, even if by happenstance. That, alas, today is little comfort to city folk in many destinations, including Ammanis and Beirutis.

It’s a cruel world. Cruel to cast out so many from their homes, and cruel for fearing them everywhere else. But here in the Levant, our smallness and the sheer number of incomers portends a radically different shape to our makeup and politics. We receive our distressed neighbors even as we ourselves grow poorer, more polluted, hotter, and more thirsty. Diminishing resources and bourgeoning populations in overwhelmed states are the stuff of vacuums and blowups.

I heard it a long time ago that a Chinese master said of the Levant, this geography has terrible fang shui. I wonder if we will ever prove him wrong.

****

On Another Note

You Like Emma Thomson like I do? Then you will enjoy this profile in The New Yorker.

Many journos and observers of the Israeli scene attributed the far-right electoral win in the latest Israeli elections to the recent upsurge in violence on both sides of the Green Line. The truth is the polls have been pointing to a pernicious rightward march for years, even decades. Here’s Shibli Telhami in a 2016 Washington Post article on the trends:

[the survey] found that 48 percent of all Israeli Jews agree with the statement “Arabs should be expelled or transferred from Israel,” while 46 percent disagreed. Even more troubling, the majority of every non-secular Jewish group, including 71 percent of Datim (modern orthodox Jews) agreed with the statement.

Finally, since I will be very busy with the Beirut launch of This Arab Life and related activities next week, the next post will be on Sunday, November 27.