"Lina, My Little Muslim Friend"

Last week, a Lebanese friend of mine, whom I shall call Samira, went with her daughter and granddaughter to the children’s toy department at London’s Selfridges. Upon entering the store, she was stunned to see little veiled Lina and her playmates on display.

The Muslim dolls Lina, Amira and Aamina, displayed at the Children’s toy department at London’s Selfridges

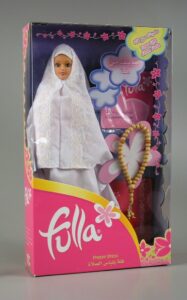

We’ve long had veiled dolls here in the region, I’ve just learned. I couldn’t find one in Beirut–yes, I went to five stores in very conservative neighborhoods–but Fulla, a Barbie-like doll, appears to be popular in Egypt and Algeria.

Meet Fulla

Samira, who is in her seventies and has been living in London for the last 50 years, is an Arab feminist of the generation who claimed the stage, or at least thought they did, in the 1950s and ‘60s. Their confident presence in the public arena as “modern” women was, for them, a promising sign that they were beginning to break barriers and change norms. Their setting was urban, their look was all Biba, but, unlike the first generation of Arab feminists, their strata was not uniquely privileged, nor was their education. Samira herself came from a struggling lower middle class family. Her father, a hajj multiple times, spent his day praying and selling textiles.

For Samira and her companions, the hijab’s surge by the 1970s was a painful repudiation of the relative autonomy and freedom they believed they had achieved. And from the start, they saw a clear correlation between this setback and a rising Islamism that made us women spear and shield on its political and cultural battlefields.

In this insight, they did not miss. There has never been an argument with women who cover up as an expression of modesty and piety, or more emphatically as an Islamist statement. There has been even little argument with women who wear the veil as a showpiece of their emancipation from “Western” cultural hegemony. It is a tad bit ironic that this very act of emancipation is a piece of cloth that itself is quite confining, but it’s a choice made freely.

There is a mass of women out there, however, who’ve never cared for the hijab but have had to don it to make their participation in public life tolerable to their family and society. They grudgingly wrap it around their face to win permission to go to school and university, to work, to walk the streets and ride the buses and engage with little fear of harassment. In this sense, the headscarf, their jailor, becomes their liberator.

And herein lies the crucial point in the never-ending discourse on the hijab: the fundamental matter of freedom of choice. By giving extreme comfort and legal cover to patriarchy and its dictates, and to misogyny and its cruelties, both our regimes and Islamists have made the veil many a woman’s only path to a more free life. In pervasively harsh political and social climates, where freedom of choice is generally not on the menu, women have found themselves bearing the brunt of societies’ frustrations and intolerances.

The saddest irony in all this is the hardest lesson as well for the women who cover up out of necessity rather than conviction. Through the many years of “religiously” having the veil on, they discover that, at least against the incessant harassments of men and systems, it offers little space and protection.

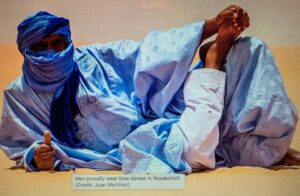

At the store, Samira promptly took photos of the dolls and sent them to a leftist English chum. Samira was looking for solidarity, but the lefty begged to differ, sending her a series of photos of women in Indian saris and traditional Peruvian and Ottoman dress. She even sent her a photo of a man lounging in a blue Daraa in the desert and playing with his toes. Little Lina’s hijab is about Muslim culture and folklore, she was obviously saying.

Photos sent by Samira’s English friend

But is it? Is calling Lina, my little Muslim friend, like calling, say, Meera in a sari, my little Indian friend? Are the hijab and the sari culturally comparable? Is Lina a nod towards diversity or a lazy stereotype?

Is there an Islamic culture or civilization that unites me, for example, with an Indian or Indonesian or Chinese or Chechen or Nigerian Muslim woman? Let’s assume there is such a wonderous tent, would the veil do well as its unifying emblem?

I don’t know, I suspect the lefty English friend would fiercely object to any reference to a Christian culture or civilization. And if she in fact thinks there is one, what kind of female dress code would best sum her up as a Christian woman? Would this culture be a sisterhood that includes Arab and Korean Christians?

Besides, “Muslim” girls are never veiled at Lina’s tiny age. So the purpose of veiling her for little ones who are not covered themselves serves what purpose exactly? Early training? It couldn’t be the promotion of diversity, because ours has long been a sea of headscarves. Or is Lina meant for English girls? The creator’s way of encouraging them to have Muslim friends, and they figure the best way to do it is to veil them, sort of like a marker to signal their “otherness”?

A tangle, this, in small parts silly, in large ones dead serious. I conclude with three works: the first, Ghost, by Kader Attia, an Algerian artist; the other two by Yemeni photographer Bushra al Mutawakil.

Kader Attia’s Ghost Art Installation and Bushra al Mutawakil’s Mother, Daughter, Doll and What If photographic series