Pining for Palestine

It happened when I started watching Losing Alice, an Israeli series that debuted on Apple TV in 2020. By the end of the first two episodes, I noticed a pining kind of curiosity carrying me through the show. The series itself was in fact very good, but I found myself gazing with wonder at these people’s lives: their houses, the views from their windows, the streets they walked, the restaurants and clubs they frequented, the port, the sea…

I was longing for a place so very close, no more than 40 minutes by plane and very near the center of my heart, and yet worlds away, unreachable, foreign, at once here and real, lost and gone. It was a pining like no other–for me.

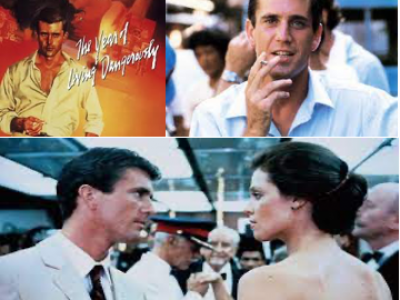

Mood is the gift of art. In 1982, my best friend Joye and I went to see Peter Weir’s The Year of Living Dangerously. The location was Sokarno’s Indonesia; the time, 1965; the weather, very hot, humid, and heavy with lust; the leads, Mel Gibson, an Australian journalist, and Sigourney Weaver, a British spy, smoking their way through love, famine, anti-communist purges, Gibson’s bungalow, the Hilton’s swimming pool and bar, and Kiri Te Kanawa’s magnificent rendition of Strauss’ Four Last Songs. The first thing Joye and I did when we stepped out of the movie theater in Washington D.C is sit in our favorite bar, talk as if our life depended on it, and light up and smoke our cigarettes with a relish familiar only to the Gibsons and Weavers of this world.

It was perhaps a year or two before, when I was silent for two long days after watching Christ Stopped at Eboli, Francesco Rossi’s portrayal of Carlo Levi’s memoir of exile in that hoary town. So was my silence after watching Asghar Farhadi’s About Elly. I am always the fascinated, invisible neighbor in any of Naguib Mahfouz’s novels. I am young and ever so fragile as I coast the South of France in James Salter’s A Sport and a Pass Time, and every time I see Georges Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, I imagine myself by the river bank with the rest of that happy crowd, taking in the sun.

I discriminate only because the page insists I do.

But that pining curiosity while watching Losing Alice evoked a mood like no other, a yearning quite simply felt and experienced, and yet unfathomable. In conversation with family and friends, I discovered I was not alone. We were all watching it with the same wonderment. Many novels about Palestine tug at the heart, but the mood of which I speak was different. The effect was not about remembrance, or endurance, or struggle; it was about landscapes and rhythms that, had history taken a different turn, would have been mine to know and live.

Soon after the 2011 uprisings began to unravel, many thought Palestine was going to fade. Loss, unbearable in its intensity and so indiscriminately inflicted, was bound to be the wellspring of many new causes. And for a while there, Palestine did fade into a backdrop of pain. Then, all of a sudden, over the past two years it started to reassert itself; in the news, yes, but more profoundly as the undisputed object of Arab love and loyalty.

I see such expressions of love anew in the children of friends who seek to repair a severed history by recording the memories of their grandparent in pre-1948 Palestine. I see it in our eagerness to watch Darin Sallam’s Farha on Netflix. I see it in Arabs, teams and spectators, in the World Cup wrapping themselves with the Palestinian flag while the rest of us cheer in front of our tv screens, on Facebook, TikTok and Insta…; I see it in the polite reminders to Israeli tv crews that Palestine, in our collective self, is alive and well.

These are not political acts in the strictest sense. They are not organized calls to action. They’re not coordinated or sponsored by any political party or state. They don’t signal any specific ideological program. They’re unrehearsed and individual declarations of devotion to Palestine that transcend politics.

And so was mine when watching Losing Alice.

****

On Another Note

There’s a Cézanne retrospective at the Tate Modern in London. Cézanne’s Withdrawal, Saul Nelson’s essay on it in Sidecar, is a wonderful weekend read.

We should not look to the Three Skulls, then, for some neat, closed statement on mortality. Certainly, the painting is a memento mori, done in the tradition of Cézanne’s heroes Titian and Poussin. But we should ask what the difference is between such a painting, done by an ageing Cézanne as the twentieth century dawned, and those of the painters on whom he drew. What was death’s social content at this point in the history of modernism? What marked it off from Et in Arcadia Ego?