The Changing Mood of The “Westward” Arab Elite

It’s always been a rather complicated relationship, the US and Arab elites. There’s nothing unusual about that between empire and those it proposes to sponsor and instruct (its allies), and those it intimidates and subverts (its adversaries). But in the Arab world, it’s been a wretched experience all around, especially for the “westward” ones in our midst.

You probably expected me to use the more common term “westernized,” but I mean to describe and not label a specific elite: those whose perspectives may diverge and clash on many issues but meet on one essential point: the expectation that the West, which almost always means its leader the US, will rise to the occasion and solve the region’s intractable problems. And the irony that the West itself is part author of many of these problems only serves to reinforce this expectation.

But for the longest time, these anxious souls have yearned in vain. Why, then, this misplaced faith in the West?

A tendency to parse history or treat it as a thing of the past (as in, what’s done is done) is one explanation. It’s hard to believe in full view of a very rich and raw record of Western hypocrisy, double dealing, and avarice. But we shouldn’t underestimate human aptitude for pragmatism and forgiveness, especially when the challenges are daunting and the saviors are few. I know that at least some of those who thronged French President Emanuel Macron when he walked the streets of Ashrafieh after the Beirut Port blast in 2019 were not Maronite subscribers to motherland France, but they pined all the same for him “to save us.”

There’s also the enduring assumption, not entirely unfounded but not entirely valid either, that the West’s democratic instincts, commitment to the rule of law, and other some such reassuring qualities appeal to its better angels and make it the far lesser of two evils. “Under whose thumb would you rather live,” the question is often asked in such discussions as if to end them: “Russia or America?”

That’s a remarkable show of magnanimity towards the US if you think about it. Because its behavior in the Arab world in the past 70 odd years hasn’t been exactly exemplary. Certainly not when it came to Palestine, the cause that has mattered the most, and not when it came to our aspirations for a bit of legroom in choosing our systems of rule and managing our wealth.

In fact, bar the 1956 Suez War, when America’s interests coincided with Egypt’s and forced the British, the French, and Israelis to withdraw their armies, the US’s track record has been consistently lousy. In whose book is the American performance in Iraq after 2003 measurably better than the Russian one in Syria post-2015? It can’t be the Iraqis’.

There’s also, of course, the sustained conditioning Arab intelligentsia has had over the long stretch of the cold war: you couldn’t float, neither in this orbit nor that. You had to choose sides. If you leaned West, you couldn’t just jump fences, however pissed you were about the US’s embrace of Israel or its habit of being such a fickle friend. As disappointing as America was, it was all you had.

Besides, when the Soviet Union bade the world farewell in 1989, there remained only one superpower in the neighborhood. In a unipolar world, the reliance on the US to do something could only grow.

US soft power has also played a pivotal role in suggesting to this “westward” elite that America cares about much more than Israel, oil, and security, the three constants in its foreign policy since World War II. Or at least that the distance between these priorities and the imperatives of intervention on this elite’s behalf is much nearer than the US thinks, if only the US could be made to see it that way. Contributions to human and civil rights organizations; the funding of UNRWA, the United Nations Refugee And Works Agency that has long provided essential services to Palestinian refugees; cultivations of rising leaders in different sectors, social investments; and the right dose of rhetoric in support of minority, gender, and LGBTQ rights, have been remarkably successful in nurturing the impression that the US can be appealed to in times of difficulty.

Some critics of this outlook pan it as amateurish and naive. Harsher detractors deem it as the foolish delusion of toadies. Both criticisms are fair to a degree, but neither pays attention to the peculiar psychology that shapes this attitude towards the US.

I was in Jordan when the multinational coalition drove back Iraq from Kuwait in 1991. Friends would talk one week about the nasty surprises Saddam Hussein’s underground tunnels held for the coalition, only to predict a grand American bargain a-la the Marshall Plan the following one.

When President Obama issued his chemical weapons redline in 2012 to Syria’s Bashar Assad only to back out when the weapons were actually used, many around me, who are fully aware of US failures in the region, were furious at the dithering American president. That the Iraqi debacle was more fresh in Obama’s memory than it was in theirs is astonishing considering the costs the invasion exacted on the region.

In the current Lebanese crisis, many observers, very few of whom are pro-American, have been mystified at US insistence, until recently, that Riad Salameh, the scandalously corrupt governor of the Central Bank, is “critical to the stability of Lebanon,” in the words of a visiting American diplomat.

It’s not suspension of disbelief that explains this bafflement by Western and US conduct, but a deep sense of helplessness in the face of our countless predicaments; equally, a lack of agency bred by age-long external meddling or involvement. What you are left with is a conviction that there’s no way out without a foreign rescue, because on your own you are bound to fall short.

And hence when the US and the West mobilize to, say, take down tyrants like Iraq’s Saddam and Libya’s Muammar Qadhafi, the initial reaction is euphoria, soon followed by astonishment at the screw up or, worse, at the sinisterism with which hidden intentions were threaded into strategies.

It’s not strange, then, that expectations of the West among this section of the elite never seemed to correct with experience and exposure.

Until now.

Stirrings are hinting of a turnabout. Impatience with Western moralizing and ridicule of its double standards in calling out violators of its ideals and values is palpable and unrelenting even among once very friendly Arab constituencies.

I am not sure what finally provoked the howling laughs and waves of the backhand instead of the usual hurt sulking, but Ukraine, Qatar, and Israel can certainly take much credit for gathering the myriad slights into what looks like a crossing.

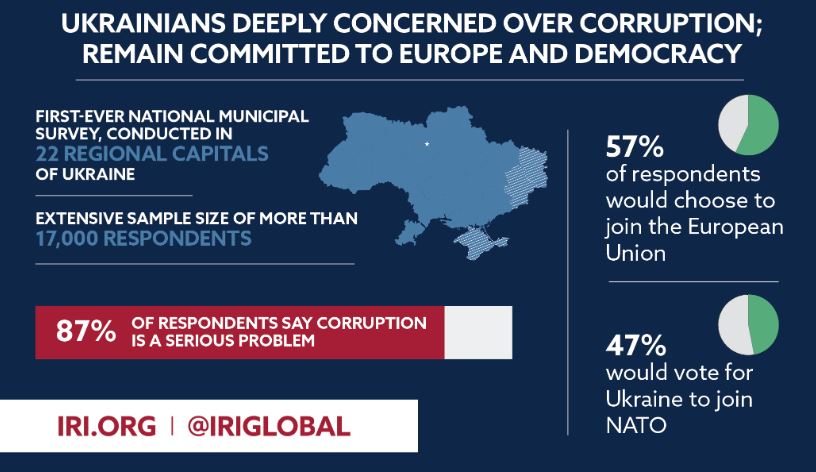

Outrage at the Russian invasion of Ukraine but longstanding acquiescence to a hideous Israeli occupation has offered a jarring example of Western hypocrisy. The dizzying speed with which Ukraine itself transformed from a kleptocracy with fascist elements in government to a bastion of democracy left the West even more wide open to scorn.

But it was in the Qatar Mondial that Europe, for one, began to seriously bleed respect. The racism that announced itself with such fury was shocking to Arabs across the political spectrum. Slurs and denigrations permeated platforms as if their owners could not abide a solid performance by an Arab country.

Add the recent eruption of violence in Israel-Palestine, with a screamingly bigoted state and its settlers competing in terrorizing the Palestinians, as the European Union and the Biden Administration offered the usual bland tut-tuts, and you had a pileup.

But the question remains: in tangible terms, what’s the meaning of all this for the West?

Hard to tell in these early days.

But I imagine that in an increasingly competitive multipolar world, glimpsed in the recent Chinese hosted Saudi-Iranian rapprochement, the “westward” elite’s defection, if it takes root, is sure to show its costs in the geopolitical bazaar of influence and ideas.

****

On Another Note

Professor Alexander Motyl thinks the collapse of Putin’s regime is likely. Here’s an excerpt from his argument. I remain unconvinced.

If today’s Russia follows these countries’ footsteps into collapse, it will have little to do with the Russian elite’s will or Western policies. Bigger structural forces are at work. Putin’s Russia suffers from a slew of mutually reinforcing tensions that have produced a state that is far more fragile than his braggadocio would suggest. They include military, moral, and economic defeat in the Ukraine war—but also the brittleness and ineffectiveness of Putin’s hyper-centralized political system; the collapse of his macho personality cult as he faces defeat, illness, and visible age; the gross mismanagement of Russia’s petrostate economy; the untrammeled corruption that penetrates all levels of society; and the vast ethnic and regional cleavages in the world’s last unreconstructed empire.