The Gaza Syndrome

October! The usual change of seasons and its darting dizzy spells. A few days and they will dissipate, I said to myself. But they stayed for weeks, then months.

The doctor said it could be the crystals in my left ear. My sister’s problem since her teens, would you believe? What would make them misbehave with me now, I wondered?

I mentioned the dizziness during a girls’ outing one evening, and most, it turns out, suffered the same. I mentioned it one morning to my brother all the way in Dubai. The same. Friends in Cairo and Amman, in Paris. Family in London as well. And so on.

By January, we took to calling it the Gaza Syndrome. A manifestation of heartbreak in the midst of incessant activism in whatever capacity available to us; the dismay of the helpless a few miles away from the epicenter of the slaughter.

A show of love!

We forget. Once upon a time, not so long ago, people across the hills were kin, a stone-throw away before the borders came. Southerners, here in Lebanon, traveled often to the nearby villages and towns of Northern Palestine. Not so often to Beirut, it was so far up the coast.

In Jordan, the affinities form the fabric of society. The majority of its population once harked from the other side of the Jordan River–the enduring legacy of the Israeli conquests of 1948 and ’67. And that’s but one of the rich inheritances of intimacies.

For many of us in this neighborhood–call it whatever you like–to identify with the Palestinian cause is to identify with oneself. Something Israelis need to fathom, finally. It’s beyond politics, though, paradoxically, the granularities of the cause itself are so very political.

Palestine, for example, is a prickly issue for us Lebanese, but then I can’t think of a single issue that isn’t. All the same, this blessed place, which never quite dimmed in our imagination, conjures a whole different set of emotions. Betrayals, blood, mistakes, and breathtaking cynicism do stain its surface, like gore besmirches hallowed grounds. The grime is integral to its history, and yet its sacredness is forever unsullied.

The remarkable thing about Gaza and its tormented people is how they have become, in the words of my friend Karim, “a test of character.” To care is to transcend; to be human above all else, as “human” in our loftiest ideals is understood. To be just and discerning because the truth is grand and self-deception is, by its very nature, lowly. To have a moral scope that is much larger than the petty boundaries of politics and identity.

Gaza, in this sense, is defining. Where you stand on it is who you are. Cruelty is always an invitation to declare a position; cruelty of genocidal magnitude insists on a baring of the soul, a show of the true self. And how much have we learned about ourselves and others in the past three months! How much have those who have never really known it, learned about Israel’s character, its army’s, its people’s; about the extraordinarily brave voices, however few, in its midst?

We’ve parted ways with old chums and break bread now with American Jews and youth in numbers their parents dare not grasp, let alone explain. We’re one with Ireland, Belgium, Spain, and Norway. And, on Gaza, they are oceans apart from England and Germany. Biden, to his White House Interns, was a certain kind of man before October 7, and quite another after it. Who would have thought that so many of the State Department’s cadre would discover the same about their president’s character? And so on and so forth.

Gaza, in this sense, is also very personal. Between those who abhor it and those who adore it, it swings, dehumanized and lionized, between villain and hero. And while the former label deliberately takes everything from it, the latter inadvertently demands too much.

Romanticising Palestinians, expecting us to show our strength, resilience and patience throughout it all, imposes mythical terms on our experience and our everyday struggles. It obscures our humanity, reduces the depravity of Israeli violence, and ignores other forms of violence, especially the structural violence that we continue to face every day.

Our loved ones in Gaza have not chosen this violence. No one chooses to be treated this unjustly. The reality is that many Palestinians in Gaza are trying to leave, to find safety wherever they can.

It’s a lashing rebuke, Malaka Shwaikh’s “Against Resilience,” in the London Review of Books. A loved one telling us that to put her on a pedestal is to somehow render her not human.

To love Gaza, then–to love it truly and wholly–is to love, in equal measure, its strengths and fragilities. To bow to its beaten spirit no less than to its soumoud, steadfastness. To romanticize less its heroism and respect more its vulnerabilities.

To acknowledge, first and foremost, that your role as Gaza’s lover is to embrace the richness of its humanity.

There is no show of love, no test of character more meaningful than this.

****

On Another Note

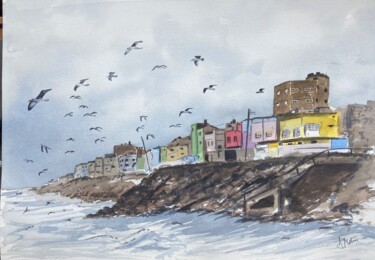

Did you know that Che Guevara came to Gaza in 1959? I leave you with this DW documentary, “Preserving Gaza’s Photographic History.” If you’re looking for a visual album of the Strip, start here.

Finally, rest your eyes on this precious photo by Kegham Djeghalian, the Armenian photographer who captured life in Gaza throughout the 1940s and ‘70s. The shadow is his, and so are the children.