The State of Us

“Stand before a picture as before a prince…Waiting to see whether it will speak and what it will say.”

Schopenhauer

Every once in a while, a lone photo emerges to render the human condition in all its pain and beauty. A vista that says it all.

Comes now one among a flood of snapshots of an earthquake that has disturbed the quiet of southeastern Turkey and added to the devastation in the north of war-torn Syria.

A small building, at once proud and defeated, teeters somewhere on the Anatolian fault line, its insides exposing the false normalcy of yesterday, the seconds prior to midnight. The remains of a living room, the clutter of a bedroom, white curtains flailing on collapsed balconies, a man inspecting the ruins of a life–his, perhaps. And yet, the building stands, its windows strangely intact, its rooftop apartment lit by the early rays of the sun or the fading shimmer of the stars. Or so the photo betrays at first sight.

I landed upon the photo in the New York Times. It belonged to a gallery of images that ran like visual commentaries on our endless hardships. But the photo, I thought, uniquely spoke to the state of us: the routine of suffering interrupted by fleeting everydayness, when it should be the other way around. This is us, all bent and broken and just about to fall under the weight of a predicament abounding with eruptions and blows.

A wreck of a place, we have. A wreck of a people we are. A region that lurches from one calamity to the other without letup or respite. What laughter and mirth there is, we steal; what predictableness foreign lands huff at, we pine for. We think we are so used to it, until an earthquake nearby unleashes misery, and even the luckiest amongst us are, by the tremors, woken to the physical and emotional exhaustion we endure. We thank the gods for the smallest of mercies in random escapes and laugh at our good luck–this time around.

It’s at least an interesting existence, we tell ourselves. And we are not wrong. It is interesting. But what does that mean really? Interesting! Can interesting not be light, without anguish and pangs? Can it not be easy on children and kind to the vulnerable? Can it not be without the color red? Can it not offer long peaceful stretches that invite a smile, however tentative?

It’s always been like this,” we console ourselves. But it hasn’t. A mess doesn’t freeze in time, nor does a good thing. There is only the look and feel of stasis, and the trend, left well alone to travel, will inexorably head downward. In choosing to make peace with our quandaries, have we not been at our most reckless and destructive?

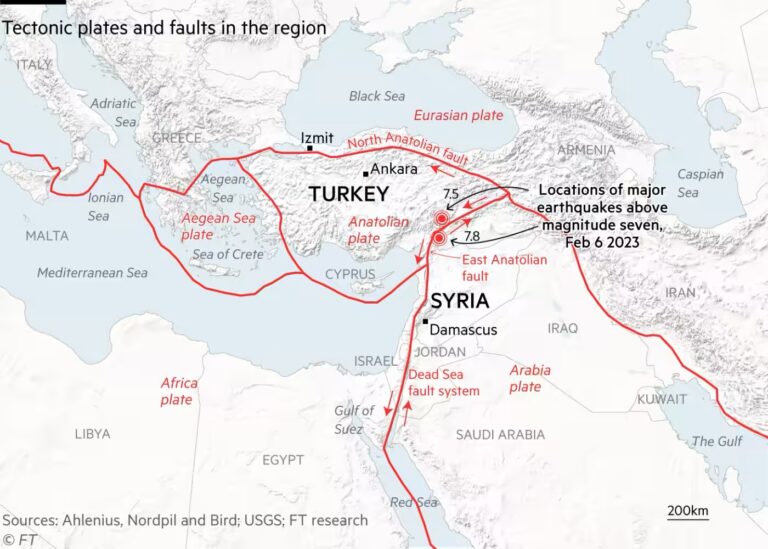

The Financial Times hosted experts a few days ago on its front page to explain this last earthquake. Apparently, “the Arabian plate is pushing the Anatolian plate westward at a rate of about 2cm per year.” A slow, relentless needling and shoving, it sounds like. The friction puts the rock masses in constant strain, eventually causing them to break past each other. The result is, of course, this fierce convulsion that repeatedly raises and uproots entire regions and their inhabitants.

The madness of geology and geopolitics so intimately intertwining, I muttered to myself as I read on.

****

On Another Note

What better read than Zadie Smith on Tár. No, not a review of but an essay on the movie. If you haven’t seen it yet, you might want to skip the article because it is full of spoilers. But what a piece it is!

Of course, not everyone who reaches middle age has a crisis or spends their middle years manipulating the young or driving anybody to suicide. But good films are not about “everyone.” They are about someone in particular, and Blanchett’s characterization of this Lydia Tár proves so thorough, so multifaceted in its dimensions, so believable, that it defies even the film’s most programmatic intentions and has reportedly sent many a young person to googling: Is Lydia Tár a real person? She is not one in the eyes of the algorithm, but she certainly is in mine. She captures so clearly the self-pity of a predator, the vanity of a predator, the narcissism of a predator, and in one remarkable scene comes to embody the act of predation itself.

If you don’t have access to the NYRB, email me and I would be very happy to gift the article to you.