The Syrian Refugees’ Predicament and Ours In The Levant

Do we Lebanese know where we stand on the issue of Syrian migrants and refugees? Not really. We have no credible public opinion polls, no in-depth, nationwide research on this community, and very few independent media platforms covering its situation with reliable facts and figures.

But do we actually have a Syrian problem? We sure do.

Do we know what it is? Not even the half of it.

In 2011, Syria’s population was an estimated 21 million. By 2022, it had shrunk inside the country to around 18 million. Per the UNHCR’s data, there are also six million Syrians who have been displaced internally. In other words, the country has experienced a violent external and internal cleansing.

Syria, therefore, may well be a mess of a place after 12 years of civil war but with a much tidier population. I am not happy at all to be using the word tidy, but I mean to make a blunt point about the massive population transfers of the past decade and their consequences in the Levant.

There is no firm data on the sect of the Syrians who sought refuge outside, but we can, with some confidence, guess that the majority are Sunni; and we can also surmise that Syrian cities and towns’ demographic texture is palpably less colorful than it was at the onset of 2011.

Much like Palestine (1948, 1967), Jordan (1948, 1967, 1991, 2003, 2011), Lebanon (1975-90), and Iraq (2003-) before it, Syria today is a place of deep psychological rifts, many fences, and heart wrenching farewells.

One hundred years into the colonial partitions that divided us even as they gathered us into this state and that in the Fertile Crescent, we are witness to yet another convulsion in our unsettled modern history.

Predictably, when Syrians fled after 2011, they aimed for safety among neighbors across the border. In the Levant, there are 674,000 and 247,000 Syrian refugees registered in Jordan and Iraq, respectively. Although, they are not likely to become citizens any time soon, they have effectively grown Jordan’s 9.5 million population by 7% and the autonomous Kurdish region’s five million people by 12%.

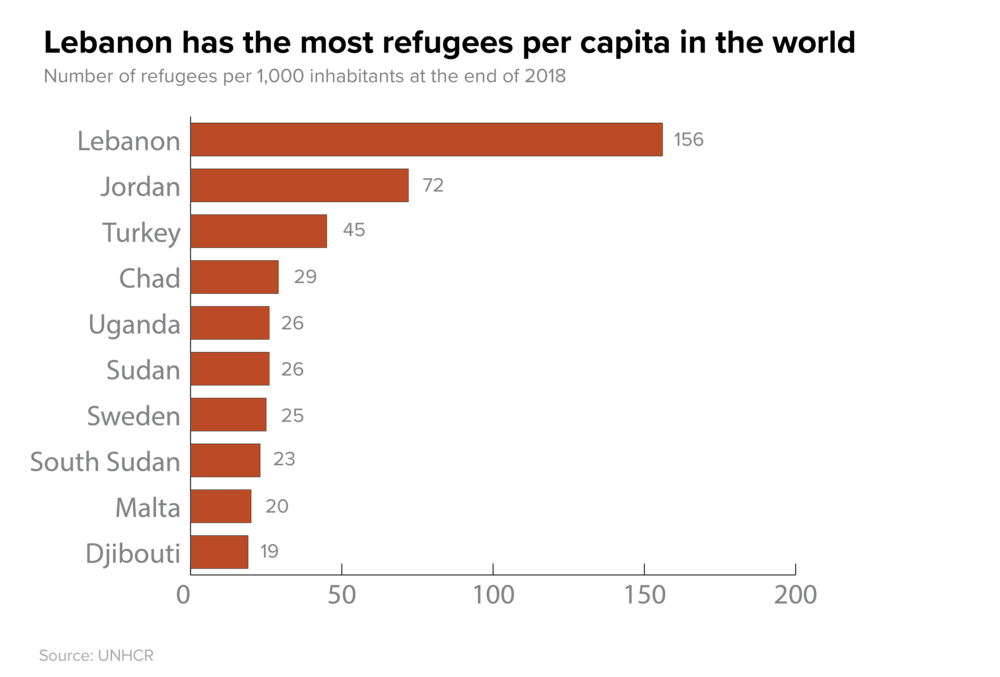

In Lebanon, as usual, it’s a tricky game of numbers. The UNHCR says there are 800,000 registered Syrian refugees, the Public Security Bureau puts the actual number at two million. Of course, we Lebanese don’t know exactly how many of us there are. The best estimates take us from 5.5 million all the way up to 6.8 million. Add the Syria refugees alone, and we will have grown anywhere between 12% to 36%. Per capita, we host the largest number of refugees in the world.

The tragic irony is that when Syrians ran for cover in each of these three countries, they were escaping from one glaringly traumatized locale into three destinations grappling with their own different grades of misery. Into already beleaguered places, the newest wave of wounded Levantines came, bringing with them a fresh set of controversies.

But whereas these refugees cause mainly economic, social, and environmental pressures for Jordan and Iraq’s Kurdistan, in Lebanon, whose demographic mix, from inception, found its worst expression in its extremely fragile politics, the challenge is more existential.

We are a people whose sects are in constant worry about numbers. So much so that our first and last official census was in 1932, although we have long been clear about the general trends: fewer Christians, more Shiites, with Sunnis holding their own.

We are also a people in constant flux. In droves, we have been emigrating to everywhere since the late 19th century. Some of us have returned, many have not. The profile of those who packed up has also changed. Among the more recent departees, the educated, the skilled, and the young have tended to dominate the ranks.

How all this will impact the makeup and prospects of Lebanon is pure conjecture at this point. I have yet to see a serious study on the profile of those coming and those leaving, Lebanese and otherwise. But the politics already threatens something terrible. As the wardens of the state egg on age-old sectarian insecurities and newly minted bigotries fed by fake news and false data, Syrians are taking a reputational, psychological, emotional, and physical beating.

But sad as this is, it is only one piece of a simmering crisis well beyond our means to solve.

Which kind of fits with our helplessness before all our problems. We think we have a good command of the facts. We don’t. We think we can deport Syrians back to Syria. We can’t. We think Syria’s president, Bashar Assad, who doesn’t want them, can be charmed into taking them back. He won’t.

Short of that, we imagine we can tuck them away, much like we tucked away the Palestinians. If you don’t give them work permits, a place in our schools, medical assistance, and financial support, they will just float in their own little universes of wretchedness, the sole concern of the United Nations and likeminded organizations. Pretty much like every other bubble we have created, we’ll create this one and move on.

The problem is that this is a mother of a bubble. And if and when it bursts in a society this troubled, a sectarianism this panicked, a state this feeble, and a politics this inflamed, the future is wide open to a jolt of the seismic variety.

How likely and how soon? Your guess is as good (or bad) as mine and everyone else’s.

****

On Another Note

Have you heard of Dr. Peter Attia? No? Well, you should. He’s the leading expert on longevity and has just published his latest book Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity. Last month, Dr. Andrew Huberman of Stanford University hosted Attia on his podcast. It’s a long conversation and well worth your time. Have a listen.