“We Miss White Bread”

Her name is Mariam. Why is she upset, the journalist asks. Life is very hard, she explains. Za’atar (thyme) is all they eat. Her father recently left for heaven, and they are stranded in a school, she and her brother.

And then the tears. “We have nothing. We miss bread…white bread.”

Who will rebuild life anew from the wreckage of Mariam’s childhood? From the ruins of her sisters’ and brothers’ in Palestine, in Syria, in Lebanon, Sudan, Yemen, Libya…?

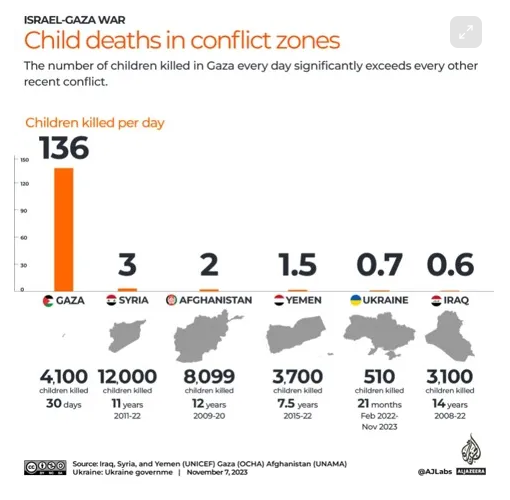

The numbers tell us that no modern slaughter has been more devastating than Israel’s has been in Gaza. For ease, we’ve taken to measuring death in daily averages and fractions: 250 in the Strip, 96.5 in Syria, 51.6 in Sudan, 50.8 in Iraq, 43.9 in Ukraine, 23.8 in Afghanistan, 15.8 in Yemen.

But of course, that excludes the living dead, whose woes are unimaginable and unquantifiable. Because how do you imagine 3.3 million displaced Sudanese children? How do you imagine that 19 million, 82% of Sudan’s youth, are without access to education? How do you imagine two million Syrian children are denied the same; that over one third have PTSD; that seven million are in need of urgent nutritional aid? How does that even compare to Yemen’s 11 million children whose nutritional deficit is just as severe?

How do the dire prospects of all these children stack up against Gaza’s now dying, orphaned, displaced, starved, and besieged on such a small patch of land?

We consider ourselves lucky in Lebanon, with only 350,000 students without access to education, not to mention our public school pupils, most of whom are at least two years behind their grade level. But we forget that we are a tiny country.

Trauma as life! An ebb and flow of anguish over the course of a century. Even if catastrophe hasn’t touched us personally, it disfigures our collective psyche and smothers our dreams. We are ever watchful and numb, defiant and helpless, nonchalant and heartbroken, resilient and nervous wrecks, repressed in our moods, brazen in our habits. All of us, to a woman and man.

I have the sense that many of us here recognize ourselves in Mariam’s tears. We do so because someone somewhere in our families’ history has experienced a kind of suffering that Mariam herself would recognize as hers. Ours is a shared memory of pain and loss different only in time and place–and luck.

Of course, history is a fountain of trauma everywhere. Violence is supracultural and so are its victims. But the sheer relentlessness of tragedy in this corner of the earth is just overwhelming. It pounds away at you every day, leaving you desperate to let go one minute and hang on the other. You weave hope from the smallest details of life even as you surrender to the infinitely larger dark realities. You find yourself seeking this specific Mariam to help, to feed, to save, as very small compensation for all the other Mariams you simply cannot reach. It is not like etching in water, not for her and her family. You can and do make a dent in her fate and perhaps even that of all those in her orbit; you might even nudge it towards a kinder “day after.” That’s not nothing. In fact, it’s something. And yet, the much grander panorama remains obstinately bleak because the forces that shape it, for all sorts of reasons, will it to be.

When does it all stop, you ask yourself? These never ending calamities, this constant management of crises, this messy patchwork. When will we breathe long and deep in relief, with the expectation that around the corner await days–too many to count–of mirth and mercy. You ask yourself this question not in search of an answer but to argue with despair. Because, truly, it is becoming too much to bear.

When Israel is finally satisfied that it has done its deed in Gaza, we will know things we dare not contemplate today. The same applies to every country that lays siege to your sleep. And this knowledge will impose that most daunting of questions: how in God’s name do we begin?

We begin with Mariam and take it from there.

To love Gaza, then–to love it truly and wholly–is to love, in equal measure, its strengths and fragilities. To bow to its beaten spirit no less than to its soumoud, steadfastness. To romanticize less its heroism and respect more its vulnerabilities.

To acknowledge, first and foremost, that your role as Gaza’s lover is to embrace the richness of its humanity.

There is no show of love, no test of character more meaningful than this.

****

On Another Note

When did al-Andalus last invite for your attention? Recently, I was gifted Eric Calderwood’s On Earth or in Poems, the Many Lives of Al-Andalus, and it occurred to me that it had been such a long time since I had done any serious reading on that wondrous place and its time.

Here’s Afikra’s Mikey Mhanna in conversation with Caldwell himself on “Al-Andalus, examining it as both place and an idea which is productive in memory, culture and politics.”