What's in A century?

I am not sure how many of us Arabs are aware that, in 1920, our Levantine forefathers were the authors of a constitution that decreed Islam merely as the official religion of the king, omitted any reference to Islamic law, and arrogated to religion authority only over religious affairs. To civil statutes, it affirmed, goes the governance of the civil state.

The constitution, in effect, established the separation between religion and state as a cornerstone of the Syrian Arab Kingdom, which hoped to encompass Syria, Jordan, Palestine, and Lebanon. Notably, it was the tenacity and nimbleness of the president of the elected Congress, Rashid Ridda, one of that era’s highly respected Islamic reformers, that ensured the constitution’s passage. He presided over a feisty debate between the conservative and liberal blocs and then hammered out a hard-fought compromise between them that saw the birth of the modern Arab world’s first progressive charter.

The clauses that shaped the democratic character of the “representative monarchy” were no less audacious than those that defined its secular orientation.

This aspirational moment died in its crib, of course, along with King Faisal ibn al Hussein’s Syrian Kingdom. As we all know, it was not a natural death. The French and the British had connived to strangle it as it drew its first precious breath.

As the years progressed and our troubles multiplied on every front, and with them our myriad defeats, an army of cultural and religious warriors, at a loss for solutions, arose to insulate us from every “foreign corruption” aiming for our soul. To ensure a decisive victory, they went first for our right to dissent in safety. Inevitably, once perfectly respectable terms, like secularism, civil rights, human rights, the civil state…, turned into the tools of the devil himself, here to contaminate our morals, corrode our traditions, insult our religion, and assault our identity.

For the better part of the past 100 years, this has been the quality of our discourse. And even more so since the mid-1970s, the louder these warriors’ vehemence and denunciations, the fainter the ripostes. If Ridda and his companions were to make an appearance now and advocate for their 1920 constitution, they would be declared foreign stooges and apostates.

That the acclaimed constitutional rights of yesteryear would progressively become the enemies of Islam and tradition and society and family encapsulates rather neatly the trajectory between that early hour of possibilities and this dire reality.

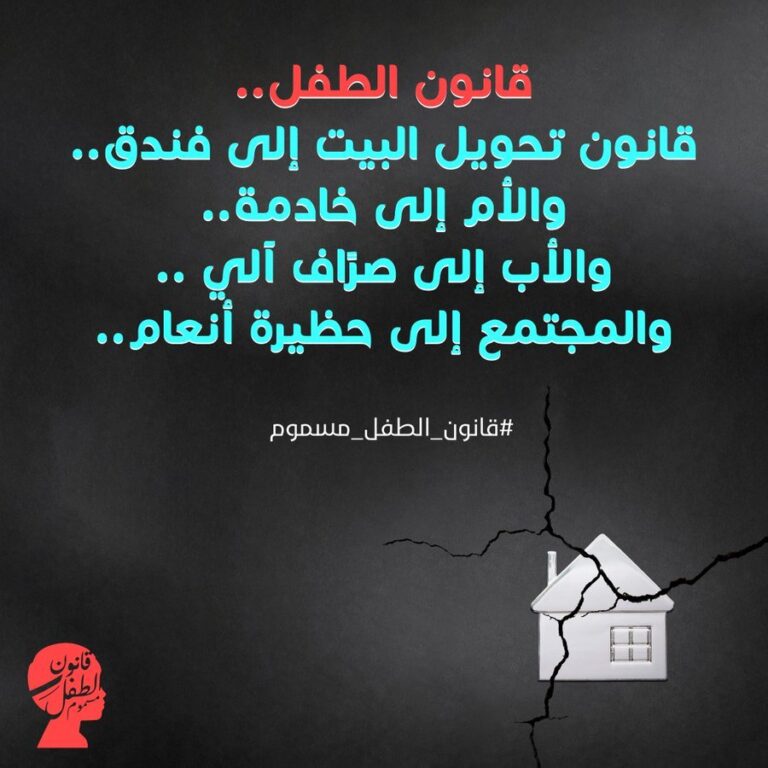

Why, for example, would the Universal Convention on the Rights of the Child, which was ratified by the Jordanian Parliament in 1991 and subsequently published in the official Gazette in 2006, raise all hell today as the state finally moved to codify it into law? Why would rights designed to strengthen legal frameworks that safeguard our children as citizens in their own right trigger such terror among certain constituencies?

Why contrive controversy where none truly exists and provoke polarization around a reform that, by its very purpose, should enjoy unanimous support? How is legislation designed to protect the child against all manner of abuse an invitation to sexual promiscuity? How are codes that cite Jordan’s existing personal status laws, whose main source is Sharia, in any way offensive to Islam?

How is it not the meanest irony that the recent murders of female students, Naira Ashraf and Salma Bahgat in Egypt and Iman Rashid in Jordan, by their rebuffed suitors is such a glaring feature of societies that have grown steadily more conservative and religious?

What would prompt, here in Lebanon last June, our interior minister to instruct the directorates of internal and general security to “ban any gatherings aimed at ‘promoting sexual perversion’…citing no legal basis, to determine that such gatherings violate ‘customs and traditions and ‘principles of religion’”? This, in a state that is collapsing under the weight of its ruling elites’ obscene moral, political, and financial excesses.

What would goad many Hezbollah followers to welcome or justify the attack on Salman Rushdie by a Lebanese-American man (“a lone Shiite wolf,” as journalist Hazem Ameen has perhaps presciently called him), 33 years after the fatwa was cynically issued?

Each of these snapshots of grievance and fury has its own special story, no doubt, pretty much like its mother country. And yet, seen together, along with a mass of similar incidents over the years, they can’t but betray a culture and a religion’s deep insecurities about their place—not in the world at large, but here among their people. Incapable of an open and free and confident conversation with those on the other side of the aisle, our cultural and religious warriors go to war. They are constantly at war, constantly aggrieved, constantly beleaguered, constantly offended, by every new idea, every demand for a right, every maverick book, every joke, every woman who dares to claim her voice, or walk free, or say no.

In writing about the Rushdie attack in al Akhbar, Asaad Abu Khalil was right in saying that all too often supporters of “the [Hezbollah] resistance here and outside fall into the traps of their enemies.” This applies, of course, to all such self-anointed gladiators–everywhere. But I think this is a trap they are more than happy to fall into. What better distraction than yet another quarrel to keep opposing opinions at a whisper and make even the most modest calls for the most basic rights a matter of life and death? Ours, it goes without saying.

This is, and has always been, the behavior of those who are in mortal fear that they will lose the argument, and so they endeavor to kill it before it gains the spark of life.

****

On Another Note

If you’re a Lebanese history buff and planning to read the recently published volumes of Saeb Salam’s journals, you might want to start first with Abu Khalil’s reviews in the al Akhbar. If you are not planning to read the volumes, start there all the same.

And here’s LRB’s Tom Crewe on Walter Sickert, “the most talented, most Frenchified and most influential British artist of his generation. If Impressionism became ‘tighter and darker’ in England, it was largely because of Sickert, the painter of music halls and of men and women behind lowered blinds and closed doors