Before I begin, some housekeeping.

The next This Arab Life post will be on Substack. Migrating, finally! I am hoping the interaction will be more rewarding for me and you.

To my subscribers, I am taking you with me, so don’t be surprised when you receive the post from Substack.

To readers who visit This Arab Life every once in a while, I would love to have you join us. You can subscribe on Substack when the next piece is posted, or do so now to my mailing list below, and I will take you with me.

Why This Time It’s Different

I have a little sister, whose myriad medical conditions from birth have demanded of her and us extraordinary faith, as it happens her name. Faith that perhaps the heavens might somehow relent and offer her a more merciful journey on this earth.

Every time I see her, I am stricken by an all-engulfing sadness made even more unbearable by her helplessness and ours, her family, before afflictions that won’t abate. When we are together, most times there is hardly any emotion on display beside outward love–no tears and scenes, no curses and furies, no visible laments. But always, there’s the ever-present whisper: ya haram. Mercy! I know that my three siblings feel and whisper the same.

It has occurred to me since October 7, so has the case been for us with another very dear one. Palestine! The times, over decades, we have averted our eyes and whispered ya haram at news of a people wrestling with a relentlessly cruel fate!

I have six nieces and nephews. The two eldest, a sister and brother, are in their forties and married. They are professionals in the wellbeing and human resources fields, have worked in Dubai for decades, and carry in them the traumas of Lebanon’s civil war and the 1982 Israeli invasion and bombardment of Beirut. They have encountered villainies their cousins have only read about in newspapers and books.

I have three nieces, one an artist and a mother of two toddlers, the other a designer and a globe trotter, the youngest a sound engineer. The oldest is 37, the youngest 28. All grew up outside the Arab world because that’s what this region does to many of its children; pushes them to escape into safer, quieter locales.

Before October 7, Palestine for them was what it had become for us, their elders: a sleeping wound, a silent pain. Their heart was in the right place, but their knowledge of the details of the struggle was different degrees of thin. Understandably, their concerns and thoughts lay elsewhere, quite far from psychological geographies that have known little respite in modern day.

I have two nephews, both in their thirties and married. One is an entrepreneur and lives in Dubai, the other is a filmmaker and resides in London. They grew up in Amman and are half-Palestinian. They didn’t have to catch up like my nieces, but their story is otherwise the same. They became alert to life when Palestine seemed as if it was barely hanging on to its own. So, like the rest of us, they went along with a reality that was depressingly unshakable.

Since November, none of us avert our eyes anymore, nor do we nurse our grief in quietude.

We all live, breathe, post, read, and argue Palestine.

I have a Lebanese friend, whom we half-jokingly nickname the neocon, because, half-seriously, that’s what he is. His love of the West is reflexive, his disdain for Arabhood, in all its collective expressions, visceral. He also has an abiding hatred for Islamist movements like Hezbollah and Hamas. He’s quite a well-read man, mind you; an avid student of history. Which, at the least, makes very peculiar the way he weds his forgiving attitude towards Western misadventures and historical indecencies in every Arab neighborhood to his ever so harsh judgment of Arab crimes and duplicities.

At a dinner last Saturday, we began to discuss Palestine. He turned to me and said, “I must admit I hadn’t given Israel or the Palestinians much attention for a long while now. I thought the Israelis were better than this. They are as bad as Bashar Assad.”

I have a Saudi friend who lives in Paris. She is in her early fifties. The daughter of a former diplomat, she is at home everywhere she goes. Her Lebanese husband, a close friend himself, drinks politics with his morning coffee and can’t quite sit for lunch or dinner without it. She, on the other hand, has always dreaded the very mention of it. Ever since October 7, she calls more than once a day to ask me countless questions about Israel-Palestine. On my recommendation, she has just finished Edward Said’s The Question of Palestine. Her husband, a staunch critic of Hezbollah, declared the other day a moratorium on criticism, bowing to the crucial point about Hezbollah’s serious deterrence against Israel.

I can go on forever like this. Anecdotes, of course; ones that it so happens reflect the much larger trend playing out all around us and much of the rest of the world.

This time it’s different. Why?

There is the obvious reason. The faces and voices from under the rubble in real time, the murder of children in real time, babies left to suffocate and decompose in incubators in real time, mothers clinging to the white-clothed lifeless bodies of their daughters in real time, interactive maps that reveal the purpose and toll of destruction in real time, meld into a horror so flagrant and loud it deafens all Israeli pretexts desperate to claim otherwise. The plain truth is, screaming terrors are always sure to provoke outrage and forge solidarities in ways that creeping ones don’t.

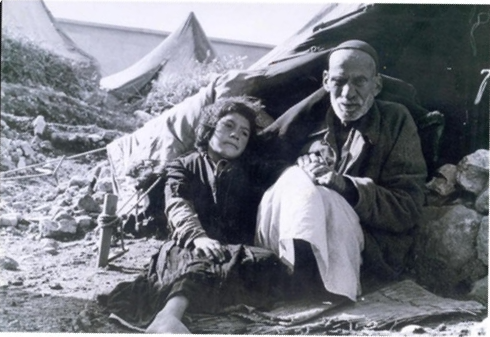

Gaza, 2023

But this is an old, much seen and much told tale–everywhere. Something altogether different in its grotesqueness has unfolded since the Hamas October 7 assaults. Almost immediately, we became witness to an Israeli ritual of killing unabashedly sinister in its method and depraved in its intent. It is not only meant to pound into the skull of the Palestinians (quite literally) and the rest of us Arabs the very might of Israel, the overpowering reality of it, but to squeeze the life out of Gazans by destroying what helps them stay put and keep living. Hospitals, schools, libraries, courts, roads, doctors, nurses, teachers, poets, journalists, every type of infrastructure and human skill a people need to survive have been decimated, and over 1.7 million Gazans have been forced into ever smaller spaces on the strip.

Attending the Israel Defense Force’s campaign has been a spectacle of Israeli hate, insatiable vengeance, and racism that permeates top of the charts songs, malevolence towards Palestinian Israelis and Palestinians under occupation, hostility towards the families of Israeli hostages, and threats against anyone that dares question the macabre show of force. The performance is almost cartoonish in its hideousness, as if we are being treated to a rough-cut Quentin Tarantino film.

I don’t know if Hamas meant to goad Israel so, knowing the Jewish state was sure to outdo itself. And I doubt that Israel, in its madness, has even attempted to anticipate the unintended repercussions of its savagery. Among these is a true-to-life reenactment of the 1948 Nakba inconceivable before October 7. Now, across generations and divides and continents, we watch as a frightful history long obscured by the passage of time, dominant Israeli narratives, and distance becomes real and contemporary.

That’s why it’s different this time. We are all back in 1948.

****

On Another Note

Tareq Baconi is an Israel-Palestine expert, whose knowledge about Hamas and the Palestinian context is without equal and whose perspective, therefore, is essential. Ezra Klein recently hosted him on his podcast, and the episode is sure to be illuminating even to those who are well-versed in the topic. Have a listen! It’s worth your time.

Henry Kissinger is dead. Here’s a man who never ever had to pay for his sins, all of them–and they are many–unforgiveable. Seymour Hersh’s obituary reminds us why. Here’s a teaser that should prompt you to read the entire piece:

“In the spring of 1973, a soon-to-retire high-level FBI official, who clearly shared my obvious distaste for Kissinger, invited me to lunch at a joint near the FBI headquarters that was a haunt for senior bureau honchos. It was a truly astonishing invitation but those were days of nothing but such moments as the Nixon administration unraveled, and so off I went. We had a pleasant talk about the vagaries of Washington and as lunch ended, he asked me to pause for a moment or two before leaving the restaurant: I would find a packet on his chair.

It contained sixteen highly classified FBI wiretap authorizations, all but two signed by Kissinger…”